Revisiting Lazy Murder

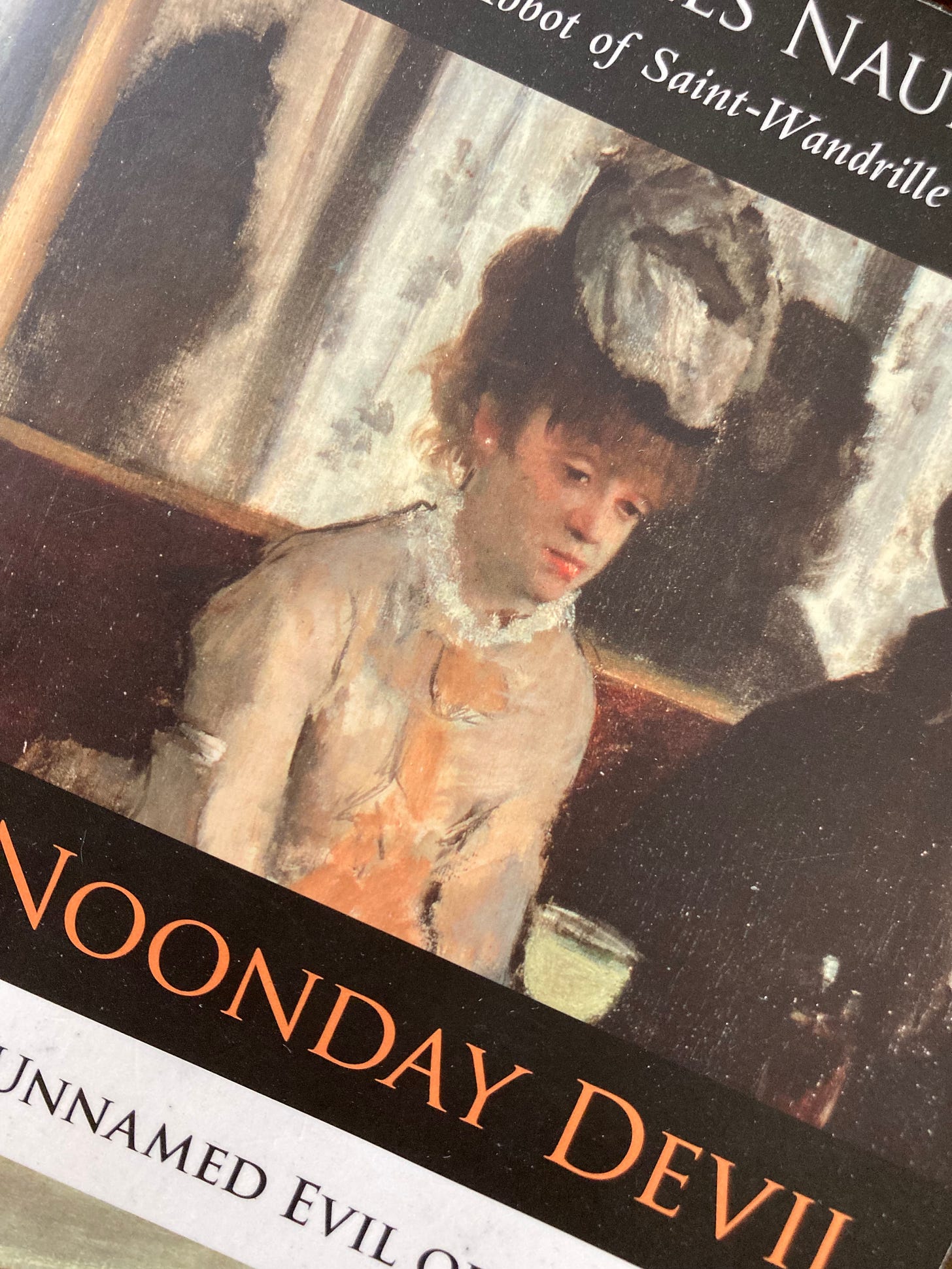

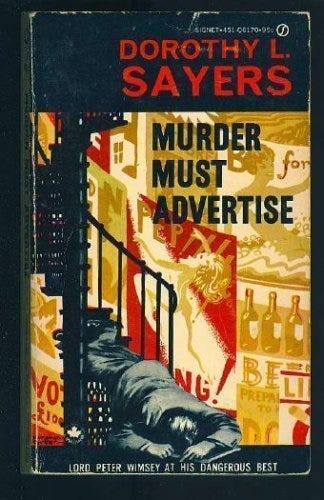

Sayer's Murder Must Advertise and Nault's The Noonday Devil with cameos from Nicholson's The Letters of Magdalen Montague and (why not?) Dante's Comedy

Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

Even scandal has lost its power to entertain. Murder and mayhem could not rouse interest in this jaded mind.

-Eleanor Bourg Nicholson’s character “J,” The Letters of Magdalen Montague

Two years ago, one of those stars-aligning moments, which all of us readers long for, happened; two books which I was reading at the same time began talking to each other.

Those two books were: Murder Must Advertise (RR 2022) by Dorothy Sayers, and The Noonday Devil by Jean-Charles Nault, O.S.B.

Then, as I began to write, two more books joined the conversation: The Letters of Magdalen Montague by Eleanor Bourg Nicholson, and The Inferno by Dante (translated by Anthony Esolen).

Murder was published in 1933. Noonday in 2015 (with lots of quotes from 4th-century Evagrius). Magdalen was published in serial form in 2007-2008. And the Comedy in 1321.

Sayers was English. Nault is French. Evagrius was born in modern-day Turkey. Nicholson is American. Dante was Italian.

Y’all, the written word’s ability to speak into various times and places at once, is celestial.

So what were these books talking to each other about?

Acedia.

A vice we don’t much mention; a word rather absent from our daily lexicons.

You understand, therefore, my surprise when this archaic word put a clarifying, unifying label upon—what were before—various unconnected grumblings of my daily life.

The Noonday Devil

To begin, let’s let Nault (let Evagrius) describe acedia.

And, as you read, I invite you to insert your own vocation or job title in place of the word “monk”, and see if you don’t believe that this term isn’t identifying a scratch we’re all itching from:

The demon of acedia, also called the noonday demon (cf. Ps. 90:6 Douay-Rheims), is the most oppressive of all the demons. He attacks the monk about the fourth hour [viz. 10 A.M.] and besieges his soul until the eighth hour [2 P.M.]. First of all, he makes it appear that the sun moves slowly or not at all, and that the day seems to be fifty hours long. Then he compels the monk to look constantly towards the windows, to jump out of the cell, to watch the sun to see how far it is from the ninth hour [3 P.M.], to look this way and that lest one of the brothers…[might have the good idea of coming to distract him from the monotony of his cell!]. And further, he instils in him a dislike for the place and for his state of life itself, for manual labour, and also the idea that love has disappeared from among the brothers and there is no one to console him. And should there be someone during those days who has offended the monk, this too the demon uses to add further to his dislike (of the place). He leads him on to a desire for other places where he can easily find the wherewithal to meet his needs and pursue a trade that is easier and more productive; he adds that pleasing the Lord is not a question of being in a particular place: for scripture says that the divinity can be worshipped anywhere (cf. John 4:21-4). He joins to these suggestions the memory of his close relations and of his former life; he depicts for him the long course of his lifetime, while bringing the burdens of asceticism before his eyes; and, as the saying has it, he deploys every device in order to have the monk leave his cell and flee the stadium (The Noonday Devil, Acedia, The Unnamed Evil of Our Times, 28).

Just to be sure you’re feeling what I’m feeling, I have taken the liberty of “translating” this description into contemporary circumstances; replacing the title “monk” with “mom” (again, for full effect, please translate the passage to your own state of life).

Rendering the description of acedia thus:

The noonday demon attacks stay-at-home-moms between 10 am and 2pm. He makes it look like time isn’t moving, and the day is interminably long. He compels the mother to constantly check her phone, to see if anyone wants to talk to her and distract her with anything but what’s in front of her. Then, the noonday tempter, instils in her a dislike for where she is, her home, and for her state of life. He gives her the feeling that no good or lasting result will come of doing any of her work (toilets will just need to be cleaned again, answered emails will just bounce back in a minute, butts will always need wiping, after one kid learns to read there’s always another, ad infinitum…), causing her to believe all tasks are equally pointless to put effort towards. The noonday tempter tells her: no one really cares or sees what you do. This is also the time when, should her husband or the neighbor or the lady at church or the grocery checkout clerk have been unfortunate enough to offend her, this too the demon uses to add further to the mom’s dislike of her home and state of life. He leads her on to a desire for other places where she can easily get more recognition and find an easier and more productive life. For Scripture says God can employ His servants anywhere, does it not? Surely it doesn’t have to be here? The temptation of acedia joins to these suggestions the memory (or the social media images) of her high school or college friends, and her former life; he depicts for her the long course of her lifetime, causing her to borrow trouble from tomorrow, while bringing the burdens of the ascetic, hidden, mom life before her eyes; and, as the saying has it, he deploys every device in order to have the mother leave her home and flee the stadium.

Everyone with me now? Everybody also saying “ouch” alongside me? Anyone else ever had moments like Julian from In this House of Brede (RR 2023) when, despite having given years of one’s life to a thoughtfully discerned vocation, one is tempted to fly after flashier, more obviously-charitable work?1

Acedia in Our Daily Lives

Now that we have that vignette of acedia before us, here’s Nault to delineate the Five Principle Manifestations of Acedia:

Interior instability

“The demon of acedia suggests to you ideas of leaving, the need to change your place and your way of life” (31).An exaggerated concern for one’s health

Aversion to manual work2

Neglect in observing the rule

(i.e. the “Rule of Life” or routine or schedule or daily habits or agenda which keeps one doing what one needs to be doing today)General discouragement

In short, acedia is malaise. It’s lacklusterness. It’s boredom.

It’s despair at Life ever being less tedious than it currently is, unless…Unless you get up! You change everything! You go somewhere else. You break the schedule! You throw all plans to the wind!

Notice the quick and radical pendulum swing acedia takes us on? From lazy slumpiness to hurried, harried busyness.

Vice can hit us from both sides, from the two opposing extremes.

Acedia causes torpor (e.g. Netflix binging) one moment, and then flurried, unplanned, restless busyness the next (e.g. suddenly throwing the remote onto the other couch and announcing: let’s GO somewhere, let’s do something, let’s go buy something). But even in that sudden rush of momentum, acedia, the friction on the soul, remains; inevitably dragging against the energy within our impulsive busyness, until we (again) slow to a halt, (again) epically cataloguing all we don’t like: this place is too-crowded; there’s nothing here I want to buy; I’m hungry; there’s nothing here I want to eat; let’s go somewhere else…let’s do something else…let’s buy something else…

Murder Must Advertise

Now, let’s turn our star-gazing sights onto Dorothy Sayers, to see acedia manifested in fiction.

In Murder Must Advertise, one of the supporting characters is Dian, a sickeningly rich, beautiful, and bored woman. The following excerpts come from her interior thoughts while drinking, doping, dancing, and doing-bedroom-things, at a 1930’s party.

Dian de Momerie was dancing:

“My God! I’m bored…Get off my feet, you clumsy cow…Money, tons of money…but I’m bored…Can’t we do something else?…I’m sick of that tune…I’m sick of everything…he’s working up to get all mushy…suppose I’d better go through with it… (84, ellipses from the original)

And skipping half-a-dozen-or-so similar lines, the center of her monologuing thoughts is:

“…my God! how bored I am…” (83)

Then skipping another half-a-dozen similar lines, she finishes with:

“I can’t stand this any longer…black and silver…thank God! that’s over!”

Dian de Momerie, wealthy, attractive, and at a pull-out-the-stops party (probably between the hours of 10pm-2am), goes through the above monologue while doing one of the most profound and intimate actions of which a person is capable. And she’s bored.

Then Sayers steps away, zooming out from this excruciatingly hollowed-out woman to take in the wide, empty landscape of a whole society.

All over London the lights flickered in and out, calling the public to save its body and purse: SOPO SAVES SCRUBBING - NUTRAX FOR NERVES…The presses, thundering and growling, ground out the same appeals by the million: ASK YOUR GROCER - ASK YOUR DOCTOR - ASK THE MAN WHO’S TRIED IT - MOTHERS! GIVE IT TO YOUR CHILDREN - HOUSEWIVES! SAVE MONEY - HUSBANDS! INSURE YOUR LIVES - WOMEN! DO YOU REALISE? - DONT SAY SOAP, SAY SOPO! Whatever you’re doing, stop it and do something else! Whatever you’re buying, pause and buy something different. Be hectored into health and prosperity! Never let up! Never go to sleep! Never be satisfied. If once you are satisfied, all our wheels will run down. Keep going - and if you can’t Try Nutrax for Nerves! (84-5)

Advertising acedia.

In a note on the flatters of the 8th circle of Hell, Sayers says:

These, too, exploit others by playing upon their desires and fears; their especial weapon is that abuse and corruption of language which destroys communication between mind and mind. Here they are plunged in the slop and filth which they excreted upon the world. Dante did not live to see the full development of political propaganda, commercial advertisement, and sensational journalism, but he has prepared a place for them.

(The Divine Comedy 1:Hell, footnote to Canto XVIII, pgs. 185-6)

It sure makes you want to disconnect.

But also—to go back to Dian, to the person—it makes me want to run back in time to girlfriends, to roommates, to co-workers, to girls-I-only-saw-once-at-a-bar-who-were-desperately-hoping-for-someone-to-think-they-were-pretty-enough-to-be-laid, and also to my own little, wanting-to-be-loved-self, and give each of these souls a hug; or in some other such way shake the acedia from the soul.

How to take a person hollowed-out by the mantras of society—by the sales pitches of acedia— and show them/ourselves/our children that we are inherently hallowed?

How do we expose the falsehood of trying to buy something different or move somewhere different or do something different in order to scratch an itch that isn’t on the outside?

For me, Sayers is like one of those long, skinny, wooden sticks with the little hand on the end. She’s like a spiritual backscratcher, like a little hand pointing one tell-tale finger at the exact place that was bothering me.

Letters of Magdalen Montague

And then, I read Magdalen.

Dian speaks from the 1930’s, post WWI and ramping up to WWII. Nicholson’s “J” writes to a friend from a similarly acedia-ridden-soul, but from 1902, prior to either world war. (Meaning, we can’t blame the disillusionment of world war for acedia’s existence):

Yes, my friend, I have fled sodden London and become, for the sake of my health, a temporary expatriate. I find the rest of the world as tedious as London can ever be, in season or out. I am not surprised. The world has been dull for as long as I have known it, and I am not so arrogant as to suppose that it was not dull before I graced it with my presence.

“How goes your time abroad?” That is the established question, and therefore you must ask it. I answer, “It is dull.” “How do you like Budapest?” That is your next question. We shall obey the laws of polite society, not out of respect or devotion to their arbitrary rule but because there are no original remarks left to us. I reply, “I do not like it.” “How long shall you be away?” Perhaps you may proffer this question next, as it is quite respectable and used in the best houses. “Forever,” is my response, “or, at least, until such time as I waste away from boredom” (31-32).

Notice that those five tell-tale, scratchy “manifestations of acedia” are all here:

Interior instability? Check. He has literally traveled over 1,000 miles to escape his discontent and malaise.

An exaggerated concern for one’s health? Check. Health is mentioned in the first line as his purported reason for leaving.

Aversion to manual work? Check. Not obvious here, but very obvious in the pages prior, that “J” is a bonafide dandy who would distain any “ungentlemanly” efforts which required physical use of one’s body.

Neglect in observing the rule? Check. “J’s” letters are vignettes of meandering from one social situation to another, displaying a complete absence of any rule, routine, or semblance of a plan for his daily life. He wanders about, waiting for someone or something else to entertain him.

General discouragement? Check. It’s dripping from every line of his prose.

Dian and “J,” two people equally stuffed full of the best money, society, and education the world had to offer, and they are bored. Buying cheap thrills. Acedia rampant.

The Inferno

And then, to prove that the 20th century couldn’t contain this vice, Dante shook me with what must be the most metanoia-inducing image of lacklusterness I have ever read. The scene is on the outskirts of Hell; the focal point is upon those “small-souled” individuals who committed themselves to nothing in Life, and so were condemned to be nothing for the rest of eternity.

There sighs and moans and utter wailing swept

resounding through the dark and starless air.

I heard them for the first time, and I wept.

Shuddering din of strange and various tongues,

sorrowful words and accents pitched with rage,

shrill and harsh voices, blows of hands with these

Raised up a tumult ever swirling round

in that dark air untinted by a dawn,

as sand-grains whipping when the whirlwind blows.

Said I —a blind of horror held my brain —

“My Teacher, what are all these cries I hear?

Who are these people conquered by their pain?”

And he to me: “This state of misery

is clutched by those sad souls whose works in life

merited neither praise nor infamy.

Here they’re thrown in among that petty choir

of angels who were for themselves alone,

not rebels, and not faithful to the Lord.…

And I: “Teacher, what weighs upon their hearts?

What grief is it that makes them wail so loud?”

And he responded, “A few words will do.

These souls, immortal, have no hope for death,

and their blind lives crept groveling so low

they leer with envy at every other lot.

The world allows no rumor of them now.

Mercy and justice hold them in contempt.

Let’s say no more about them. Look, and pass.”…

I had not thought death had unmade so many.

Inferno 3.22-39, 43-51, 573

I sat back in my reading chair. Here was the rebuttal to mantra, “As long as I’m a decent human, and not hurting anybody, it’s all good.”

No, I thought. No. The stakes are so much higher. Infinitely higher. If I don’t use the gifts that have been given me, if I bury my talents in the field, afraid to use them lest I fail, I don’t just end up “kinda-good,” or “coulda-been-a-bit-better.” No, I fall to chasing nothing for the rest of eternity.

Because they followed nothing on earth, now, in hell, they chase a swiftly moving banner, which races about without ever stopping. It is an empty sign, a meaningless cause, a flag with nothing printed on it

(Jason Baxter, A Beginner’s Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy, 23).

Acedia, according to Kierkegaard, is the “despairing refusal to be oneself.”4

So, for example, if you were given the gift of writing, you must write. You cannot “prefer not to,” out of fear of not being the next Shakespeare. You can’t abstain because you might not be great. We must be humble enough to fail, or to merely be a lesser talent. But the options aren’t: Be Shakespeare, or don’t be a writer. If you’re a writer. You must write. Even if it means being only a “small stream,” as L’Engle phrased it in Walking on Water (RR 2024). Better be a small stream than a dried up creek bed.

To paraphrase C.S. Lewis: Use your gifts, and worry not about what posterity will decide as regards your particular niche in the hall of human fame.

But to opt out of doing the daily duties and to instead fall into acedia, means being like those empty souls who never used their talents, who never entered the stadium, and who now (at least in Dante’s imagination) eternally run a meaningless race.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

-Theodore Roosevelt

Those cold and timid souls…anything but being nothing!

To fully connect acedia, and Dante, and Sayers, Baxter says that both C.S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers were greatly influenced by the quoted passage from Canto III. Quoting Sayers thus:

The sixth Deadly Sin is named by the Church Acedia or Sloth. In the world it calls itself Tolerance; but in hell it is called Despair. It is the accomplice of the other sins and their worst punishment. It is a sin which believes in nothing, cares for nothing, seeks to know nothing, interferes with nothing, enjoys nothing, loves nothing, hates nothing, finds purpose in nothing, lives for nothing, and only remains alive because there is nothing it would die for.

-“The other Six Deadly Sins” in Creed or Chaos?

Now, if you’re like me, you’re crying out: I’ll do anything but be nothing! I hear you Sayers, I hear you Nicholson, I hear you Dante, I’ve understood you Nault, I will clean every toilet, patiently respond to each too-quickly-boomeranged email, wipe every butt, and calmly sound out “r-a-t” as many times as the Good Lord (and my 4-year old) asks me to.

So, since we’re all equally motivated, let me provide, as a closing, Nault’s five ways to defeat acedia.5 (Because great enthusiasm needs order and planning or it will burn out, like any other busy-acedia fit.)

Five Remedies for Acedia

My friends, if you find yourself, between the hours of 10 am and 2 pm, monologuing like Dian or bemoaning like “J,” do one (or all) of these five things:

Cry

[Tears] are an acknowledgement that one needs to be saved, that one cannot go it alone. The little child weeps when he is discouraged, when he needs help, when he needs to be loved. The same goes for adults who, somewhere deep down, remain children. To weep is to acknowledge that one needs to be saved (Nault, 37).

Pray and work

Once when Antony was [sitting] in the desert [he fell into] boredom and irritation [acedia]. He said to God, “Lord, I want to be made whole and my thoughts do not let me. What am I to do about this trouble, how shall I be cured?” After a while he got up and went outside. He saw someone like himself sitting down and working, then standing up to pray; then sitting down again to make a plait of palm leaves, and standing up again to pray. It was an angel of the Lord sent to correct Antony and make him vigilant. He heard the voice of the angel saying, “Do this and you will be cured.” When he heard it he was very glad and recovered his confidence. He did what the angel had done, and found the salvation that he was seeking. (Nault quoting The Desert Fathers: Sayings of Early Christian Monks, 39).

Contradiction (the antirrhetic method)

This is about confronting the temptation of acedia using the method that Christ utilized in the desert against Satan, in other words, the use of a verse from Scripture to confound the devil (Nault, 40).

Or, here’s how Father Philippe describes this remedy:

One of the dominant aspects of the spiritual combat is the struggle on the plane of thoughts. To struggle often means opposition between those thoughts that originate in our own spirit, or the mentality of our surroundings or even sometimes from the enemy himself (the origin of the thoughts is of little importance) and which cause us disquietude, fear, discouragement and, on the other hand, those thoughts that could comfort us and reestablish our peace. In view of this combat, happy is the man who has filled his quiver (Psalm 127) with arrows of good thoughts, that is to say with solid convictions, based on faith, that nourish one’s intelligence and fortify one’s heart in times of trial…all the reasons that cause us to lose our sense of peace are bad reasons (Father Jacques Philippe, Searching for and Maintaining Peace, 13, emphasis original).

Meditate about death

I told you earlier that there was a temporal dimension to acedia. Now the thought of death, precisely, gives meaning to passing time, restores a linear orientation, gives it a sense, in both senses of the word: direction and signification (Nault, 42).

The Inferno is filling this role for me right now. “I had not thought death had unmade so many” (Inferno 3.57).

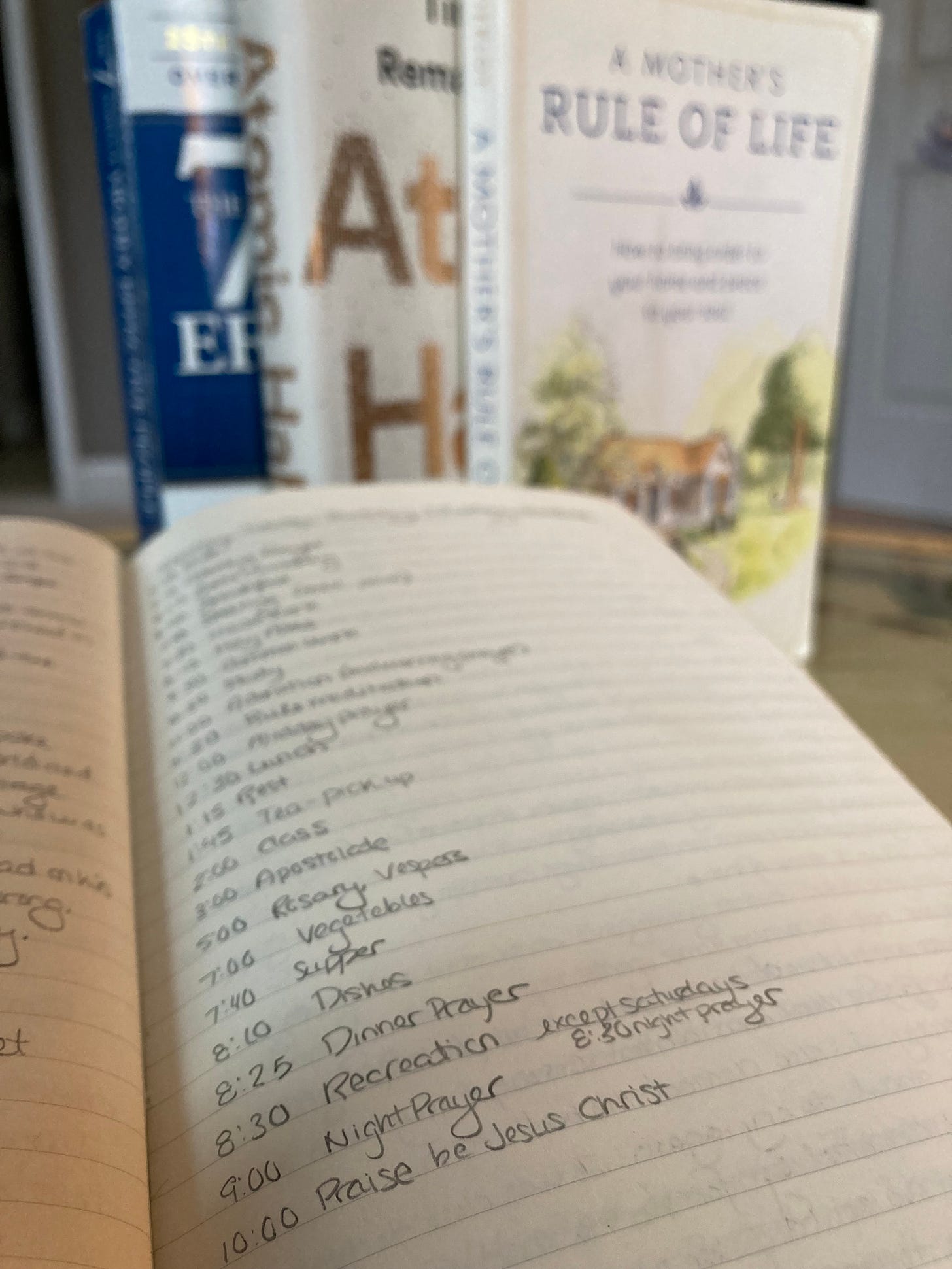

Persevere

"The handrail is fidelity to one’s everyday routine, fidelity to one’s rule of life.” (43)

The Rule of Life— what a gift I have found it to be.

My first encounter with a Rule of Life, was when I was 22 years old, and staying with the Missionaries of Charity (Mother Theresa’s nuns) in Rome. I had arrived world-weary and acedia-pummeled. While there, Christ brushed me off, and restored me. One of the first things I wrote down to bring away with me, as a crucial tool to maintaining connection with Christ, was the MC’s Rule of Life. Pictured above is the notebook I copied their Rule into. Since then, I have used it as a framework, and adapted it to the changing needs of my own daily vocation. The concept of a daily plan gave me the framework I needed to step back and ask who am I? What is my purpose? Where am I going? And then, having answered my ultimate vocation, I was able to plan out the reasonable, right, and just amounts of time to prescribe to prayer, daily chores, children’s education, developing and using my individual gifts, reading, leisure, etc. This Rule is the “handrail” that ensures one does not fall into the pit of wind-whipped nothingness, nor rocket away from one’s daily duties in a blind, Sister Julian-like flight towards some “other good” that is not one’s calling.

The best resources I have found for building this Rule are: A Mother’s Rule of Life by Holly Peirlot and Autumn Kern’s Common House and The Commonplace podcasts. Additionally, for habit training within a Rule of Life, I have found these two books helpful and invigorating: the classic, Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey; and, the more recent, Atomic Habits by James Clear. Both are good audiobooks, and both work well within the larger God-oriented framework of a Rule of Life.

I would love to hear any resources you have found helpful in ordering your daily life.

Going Forth

So my friends, lest we, through pure and simple selfish laziness, murder our own souls, let us instead go forth to cry, pray & work, draw from a filled quiver, remember that we will die, and persevere in our Rule of Life.

“Anything worth doing, is worth doing badly.”

-G.K. Chesterton

Do the hard work to make virtue habitual.

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

If you would like to make a small contribution to the work we’re doing here at Reading Revisited, we invite you to do so with the Buy (Us) a Coffee button below. We so appreciate your support!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, we appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running and we appreciate it!

If you didn’t read In this House of Brede with us, here’s additional context: After years of preparation, Sister Julian is mere months away from taking her final vows at a Benedictine Monastery, when her brother (who knows very little about church history, the personal history of the nuns in front of him, or the value of contemplative prayer) convinces her to leave the Benedictines (who take a vow of stability, vowing to commit to becoming closer to God in this place) and become a missionary in foreign lands.

Obviously foreign mission work is good. But there are times when one good will tempt us from another good. When the good we are not called to will tempt us from the good we are called to.

Interesting, but not immediately applicable to this essay: Acedia can manifest itself as laziness, or excessive business. Doesn’t that sound familiar? This will be the topic of a follow-on essay tentatively titled: Leisure: Antidote to the Busy Murder of Christmas.

I acknowledge that in Canto VII, the Fifth Circle of Hell, there is an explicit description of the “sullen” or those with acedia. This will be touched on in greater depth in the follow-on essay: Leisure: How to Kill Lazy Murder.

Sickness unto Death, p. 74ff (as quoted in Josef Pieper’s Leisure The Basis of Culture)

Worth reiterating: I am listing the 5 remedies for acedia, not Aquinas’ 5 remedies for sorrow, which are awesome, and which are: pleasure, tears, friends, contemplation, and sleep & baths.