Why Read Shakespeare (Othello Version)

Virtue? A fig! 'Tis in ourselves that we are thus or thus. To thine own self be true.

Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

We have turned on paid subscriptions which will allow you to support the work we are doing here as well as receive Read Along Guide PDFs each month, voice recordings of the Read Along Guides and Essays, and we are working on (printable) bookmarks for each book.

We have a Christmas Discount on Paid Subscriptions. This gets you $2-3 off each month(depending if you do a monthly or yearly subscription). That price will last as long as you keep subscribing (it will never randomly go up, I promise)! So if you've been on the fence, between now and January 6th might be the best time to subscribe!

Several years ago, my sister (who was at that time a high school sophomore) sent a frantic email requesting urgent help on her due-next-day paper, the prompt of which was, “Is Shakespeare still relevant?”

Then, as now, it’s difficult for me not to daydream about concluding our 8-hour Christmas drive up to Cincinnati with a visit to that school in order to grab that English teacher by his lapels (which he probably does wear), and shake him into less ridiculously banal prompts.

However, I will concede him some ground.

In graduate school, I got the impression that most of the scholars I interacted with were seemingly so disconnected from the idea that one might need to defend the humanities, that they had almost lost the ability to do so. And in losing this need to constantly re-check the metaphorical compass, it appears to me that many humanities programs are losing their way, ceasing to have any true objective, and therefore becoming more and more consumed with less and less meaningful minutia.

Therefore, to return to Shakespeare, it is perhaps not entirely useless or banal (to reuse my own word against myself) to remember why we read him, or at least to remember some things which are helpful or enjoyable to keep in mind while reading him.

A note on history:

To begin, I like placing the author in his time, so please stay with me as I summarize a bunch of things we already know.1 William Shakespeare lived from April 1564 to April 23, 1616. Straddling the 16th and 17th century, his life and work also straddled two separate monarchs of England.

Elizabeth I, daughter of notorious Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn (who Harry married in 1533 – after divorcing Catherine of Aragon, his wife of 24 years, and leaving the Catholic Church to establish himself as head of the Church of England – and who he executed 3 years later when Elizabeth was 3 years old), was queen from 17 Nov 1558 until her death in 1603. Therefore, Elizabeth I was the reigning monarch from the time our dear Will was born until he was almost 40 years old.

Since Elizabeth died without an heir, the thrown passed to James I, great grandson of Henry VII and son of Mary, Queen of Scotts. He reined from 1603-1625, the last 13 years of Shakespeare’s life and work.

After Shakespeare died, James I was succeeded by his son, Charles I, who was deposed of his thrown, and his head (big event!), by the English Civil War in 1649.

I can’t adequately express what strong shifts were occurring philosophically, spiritually, religiously, politically, etc. during this time.

A note on religion:

Joseph Pearce, in his 2008 book The Quest for Shakespeare: the Bard of Avon and the Church of Rome, has successfully laid out compelling evidence that Shakespeare was Catholic. (Phyllis Rackin briefly references scholarly arguments for Shakespeare having been brought up Catholic in her 2005 book Shakespeare & Women, just in case you wanted to hear it from a non-Catholic.)

A brief summary of Pearce’s argument: In Elizabethan England, there were Catholics who had given up fighting to be Catholic, and there were Catholics still fighting to be Catholic. It is well documented that William was born and baptized into the latter type of Catholic family, to John and Mary Shakespeare. Additionally, during his life, Shakespeare is not registered in any of the parishes of the Church of England, he donated a portion of his property to Catholic priests in his will, he was friends with well-known Catholics (notably the martyred St. Robert Southwell, a poet priest), and in his will he left all his property to only one of his daughters (the one who had remained Catholic). Here’s an article by Joseph Pearce on the topic.

And if you care for my personal opinion, before knowing any of these arguments, when deeply immersed in reading Milton and Shakespeare at the aforementioned grad school, I penciled marginal notes all along Shakespeare, saying “This man is Catholic!” Chesterton anticipated this feeling when he wrote,

“Whenever Milton speaks of religion, it is Milton’s religion: the religion that Milton has made. Whenever Shakespeare speaks of religion (which is only seldom), it is of a religion that has made him,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

Why do I think this is relevant to mention?

For two reasons.

First, because we need not leave our Judeo-Christian orthodoxy at the door when reading Shakespeare. We don’t have to jettison natural law and begin again with a blank slate of morality, asking convoluted questions like, “Does Shakespeare actually think Iago is the hero? Or, is it possible Desdemona is a symbol of repressed womanhood, and is a proto-feminist construct of the deadly consequences of marriage?”

Even in the past when I allowed these types of amoral “anything is possible” proddings into the space in my mental quarries, they weren’t helpful questions. The text did not open before me. These questions might lead to a long thesis, with a lot of evidence. But if we compare the play to a blossom, these questions left that blossom, closed, untouched, and cold, while external to the flower I remained, a mere questioner, scientifically studying the floral text to bolster my own ability to follow any premise to a logical conclusion.

No, I did not enjoy Shakespeare plays when I thought the text was bereft of any moral compass.

But now, if I settle into the thought that Shakespeare wrote plays with standard (and true) perspectives on what is right and wrong, suddenly the plays bloom. This is why I say it is helpful to recognize Shakespeare’s Catholicism. Chesterton gets at this idea better,

“The old writers knew exactly what they thought about things, and then wrote about the things. They did not write with a moral purpose, but with a moral assumption. The author of Macbeth can sympathize with a murderer; but the whole play would be meaningless if there were a moral doubt about murder,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This is what I mean by not “checking your orthodoxy at the door.” Read, keeping in mind what is known to be right and wrong, and all is a lot clearer (and more beautiful and nuanced and layered) in Will’s plays.

The second reason I find Shakespeare’s Catholicism helpful is for more Catholic-denomination-specific reasons. Example: the ghost of Hamlet’s father works better within the play when you assume that it came from Purgatory not Hell. Instead of asking questions like, “Why would Hamlet even consider taking the advice of a person damned to Hell?” Or a question like, “Is the whole play put into motion by demonic intervention?” You instead are able to say, “Oh, because Hamlet’s father died without confessing his sins, he therefore did not die sinless, and therefore required a period of purgation. Since Purgatory is a state of cleansing en route to Heaven, the ghost of Hamlet’s father is saved, and he will eventually be in Heaven. Therefore his counsel does not need to be dismissed. Indeed, Hamlet is right to heed it, as evidently this apparition is sanctioned, and has a necessary purpose in the temporal world, both personally and politically.”

Last, somewhat connected, thought: Here I’ll also note, along with Chesterton, that perhaps no one is misquoted as much as Shakespeare. Example: Perhaps you’ve seen engraved on a building, or made into a touching social media banner, “To Thine Own Self Be True.” –William Shakespeare; perhaps implying that Shakespeare was a rather trendy, moral relativist who would today say, “You do you.” While the quoted line does come from Hamlet, we do authors a disservice when we forget that they choose into whose mouths they put things. Meaning, when Shakespeare put the above quote into the mouth of the play’s fool (and not the wise fool), he was perhaps not intending people to take this as his own personal mantra – though I’m not sure he would’ve cared as much about this as I seem to, a word more on this below. :D

A note on seriousness (or not!):

G.K. Chesterton has been the most influential on my view of Shakespeare, and in the most pleasant of ways.

Chesterton contends that Shakespeare is one of the greatest authors of all time, AND that he is full of mirth, of ridiculousness, of laughter. That he is a “common man’s man,” much more instep with his Medieval predecessors than some of his Renaissance contemporaries. Therefore, while we should rightly stand in awe of Shakespeare as the greatest English author, we should also approach him as someone who wants to be approached. He was not trying to be a great man who spoke only to other great men, for the mark of a truly great man is his simplicity. As defense of this argument, note the simplicity of Christ’s fiction writing, of His parables.

So, do not forget to look to laugh in Shakespeare.

“There is in Shakespeare something more godlike even than humor: something which the English call fun,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This may help us make sense of some of the more irreverent, or bawdy scenes. Shakespeare’s faith was strong enough to withstand humor.

“The moderns who disbelieve in Christianity treat it much more reverently than these Christians [referring to Medieval monks] who did believe in Christianity…I have seen a picture in which the seven-headed beast of the Apocalypse was included among the animals of Noah’s ark, and duly provided with a seven-headed wife to assist him in propagating that important race to be in time for the Apocalypse,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

A note on poetry:

“There is a sort of speech that is stronger than speech. Not merely smoother or sweeter or more melodious, or even more beautiful; but stronger. Words are jointed together like bones; they are mortared together like bricks; they are close and compact and resistant; whereas, in all common conversational speech, each sentence is falling to pieces,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This quote, for me, summarizes why we read poetry, why we read Shakespeare, why we love to read good writing. Instead of remaining a critic on the outside saying, “That was ridiculous, no one talks like that,” after a long soliloquy by Othello, or Iago, or any other long-winded person in book. Instead, to love literature is to open oneself up to the reality of how words should be, a glimpse at what words might have been if there hadn’t been a Fall, and how words are in Scripture, and how the Word is in Heaven.

So, when we read Shakespeare (especially if we’ve already read a plot summary – more on this later), let us revel in the words, in how Shakespeare has someone say something, in the turn of phrase, or accurate description, or in the comedic or tragic timing.

“If Shakespeare were under the limitations of realism, he would be forced to make Macbeth express his depressions or despair by saying, ‘Blast it all!’ or ‘What a bore!’ And these ejaculations do not express it; that is part of the bore. But as Shakespeare had the liberty of a literary convention, he can make Macbeth say something that nobody in real life would say, but something that does express what somebody in real life would feel,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

A note on spoilers:

Be spoiled! Reading a summary before you read Shakespeare is highly helpful, and enriches, not detracts, from the pleasure of reading. Shakespeare often re-worked well-known plays, Othello, is no exception. Therefore, most of his audience would have entered the theatre knowing what was going to happen, and therefore looking forward to how Shakespeare was going to make that happen. Would he alter some small or large part of the plot? Would he remove some details or add others, and thus change the entire message of the play? Would he speed up and condense the timeline of events to “up the ante?” Would he go wild with his word-skill and phrase the whole story with such “sticky” language that one laughed, cried, and applauded at the same time?

Side note: I think a good example in current culture of how subsequent storytellers can play off of pervious storyteller’s works, is in the 2005 Pride and Prejudice movie. This most recent version could afford to move really fast, and not fully introduce characters, because it could safely assume most of its audience already knew the plot well enough to keep up. I noticed this aspect because my husband, not a big Austenite, was fairly lost throughout the whole thing. So, do yourself a favor, read a summary of the play before you read the play, then just sit back and enjoy the words.

A note (my last) on dialogue:

It’s because of Shakespeare’s mastery of dialogue, that I began to notice that some of my favorite authors were those who had mastered this craft, the craft of actually writing the quirky, disconnected, and eloquent ways of speech. L.M. Montgomery in her Anne of Green Gables series (March 2021), Harper Lee in To Kill A Mockingbird (May 2023), Leo Tolstoy in Anna Karenina (February 2022), and Wendell Berry in Jayber Crow (November 2024) are a few examples I find of excellent dialogue contained in excellent storytelling.

On the flipside, there are some books that I’ve found very interesting for the story, but which continued to lose me every time a character opened their mouth, because I kept finding myself thinking that: 1) that character wouldn’t actually say that, or 2) that’s just the author spewing their philosophy through the mouth of a character, or 3) the character didn’t need to say that, the author is just using the character as a lazy way of moving the plot forward.2

Needless to say, looking closely at dialogue has made me realize just what a tricky art it is. And Shakespeare, arguably, does it best. Currently we say, “it all comes down to communication.”

Well, that’s another way of saying, even in our daily interactions, dialoguing well is crucial.

So why not read a man who mastered it in the written word?

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

Reading Revisited ep.30: Introduction to Shakespeare with Fr. Tom

Reading Revisited ep.29: Bookish Bio of Colleen Adams (aka Jess’ Mom!)

What We’re Reading Now:

January

Othello by William Shakespeare

February

Out of the Silent Planet AND Perelandra by C.S. Lewis

March

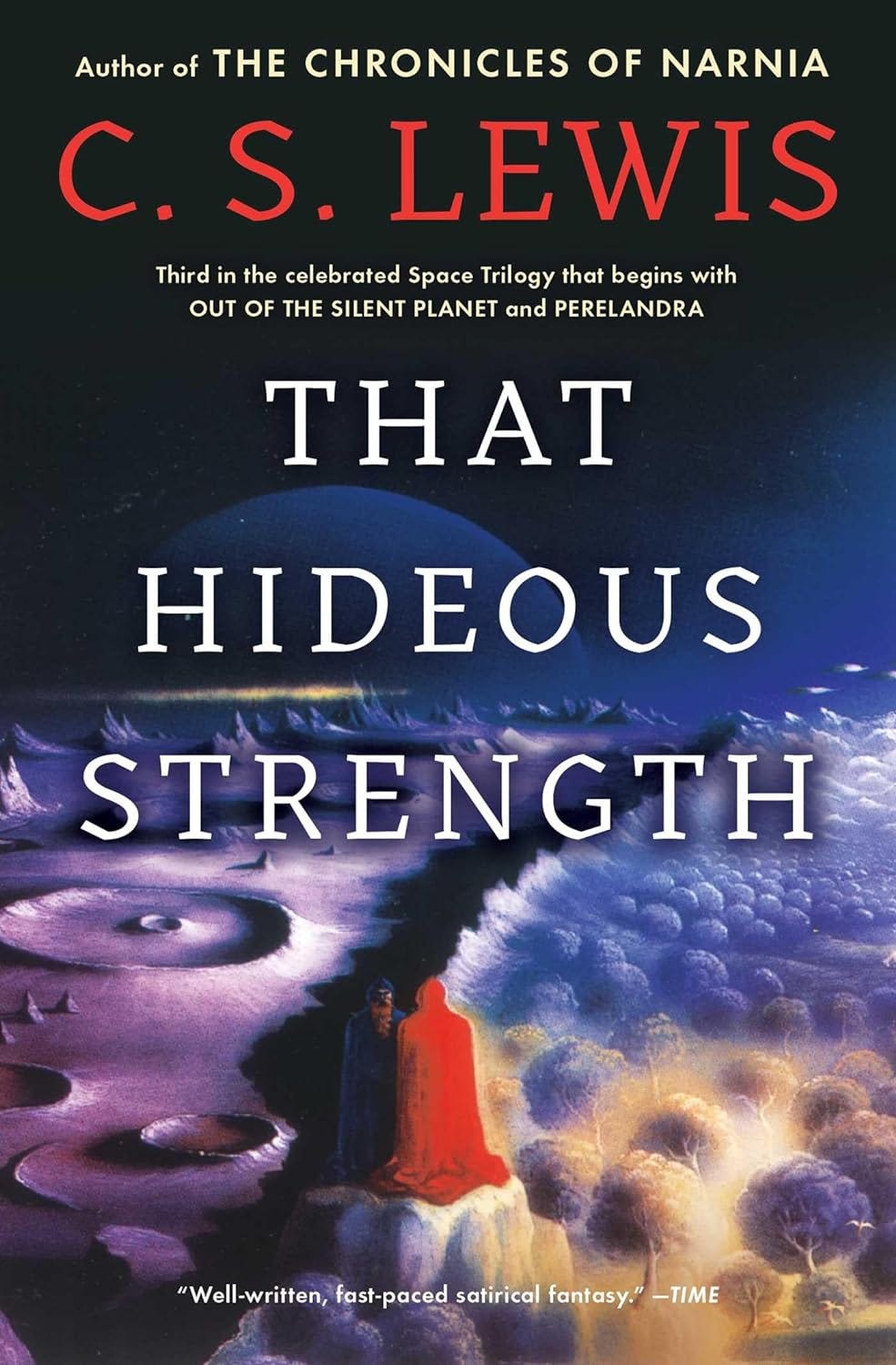

That Hideous Strength by C.S. Lewis

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us! If you have started a group and we don’t know about it, please let us know so we can get you some resources to help you out!

We have turned on paid subscriptions which will allow you to support the work we are doing here as well as receive Read Along Guide PDFs each month, voice recordings of the Read Along Guides and Essays, and we are working on (printable) bookmarks for each book.

If you would like to make a small contribution to the work we’re doing here at Reading Revisited, we invite you to do so with the Buy (Us) a Coffee button below. We so appreciate your support!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, we appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running and we appreciate it!

I expound on why I like contextualizing an author in Why (I think) I Read

The book I have in mind in this reference, is the book I use as my example of a Bad Bad Book in The Good Good, the Good Bad, the Bad Good, and the Bad Bad.

Loveeee the idea of Shakespeare as a glimpse of what unfallen language could have been like. I will 100% be thinking of that idea for a while. Definitely fits as an idea with how Tolkien approaches language/sees a connection between language and morality. For example, he noted that in “translating” orc speech, he cleaned it up-that literal orc speech would be full of curses, repetitions, insults, foulness etc to reflect their low moral stature

I absolutely loved this. I have never fully read a Shakespeare before and want to start in 2025.

Where do you suggest that I begin?