Hello Readers,

I cannot believe Christmas is only 2 days away and the Advent season is coming to a close. To be fair, this is the shortest Advent can be so it makes sense that it feels fast, but I think I feel this way every year. I hope you are all having a relaxing Saturday morning. The kids and I are watching old Christmas cartoons (many of which are very odd….you’ve been warned) while dad is out trying really hard to get that last minute Christmas deer. Very different, but seasonally appropriate activities!

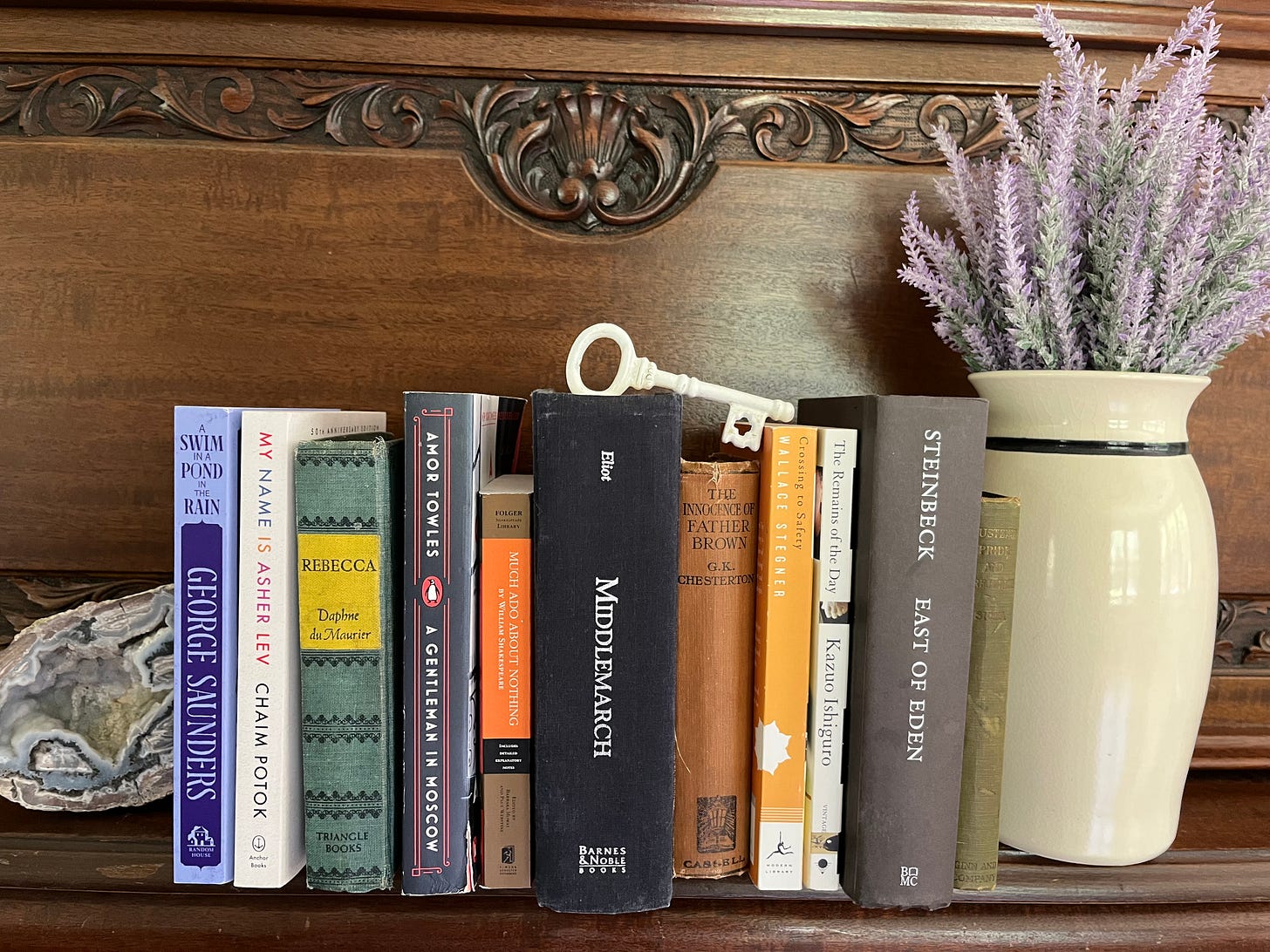

We had a lovely meeting to chat about A Gentleman in Moscow this past week and I hope you all had as much fun reading and discussing this book as I did. If you aren’t ready to be done with Towles’ writing yet, then join me in reading his other novels this Christmas Break. If you do, I would love to hear your thoughts and opinions.

Next month we are reading Much Ado About Nothing. In preparation for Shakespeare month I asked our Literature Book Club’s resident Shakespeare expert,

, to write us a little primer on reading Shakespeare. She more than delivered and I hope you all enjoy it as much as I did! This will be an essay to bookmark to come back to later, it is so helpful!Why Read Shakespeare?

By

A few years ago, my sophomoric sister (who was also literally a high school sophomore) sent a frantic email requesting urgent help on her due-next-day paper, the prompt of which was, “Is Shakespeare still relevant?” Then, as now, it’s difficult for me not to daydream about concluding our 8-hour Christmas drive up to Cincinnati with a visit to that school in order to grab that English teacher by his lapels (which he probably does wear), and shake him into less ridiculously banal prompts.

However, I will concede him some ground.

In graduate school, my humanities professors were seemingly so disconnected from the idea that one might need to defend the humanities, that they had almost lost the ability to do so. And in losing this need to constantly re-check the metaphorical compass, it appears to me that many humanities programs are losing their way, ceasing to have any true objective, and therefore becoming more and more consumed with less and less meaningful minutia.

Therefore, to return to Shakespeare, it is perhaps not entirely useless or banal (to reuse my own word against myself) to remember why we read him, or at least remember some things which are helpful or enjoyable to keep in mind while reading him.

A note on history:

To begin, I always like placing the author in his time1, so please stay with me as I summarize a bunch of things we already know. William Shakespeare lived from April 1564 to April 23, 1616. Straddling the 16th and 17th century, his life and work also straddled two separate monarchs of England.

Elizabeth I, daughter of notorious Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn (who Harry married in 1533 – after divorcing Catherine of Aragon, his wife of 24 years, and leaving the Catholic Church to establish himself as head of the Church of England – and who he executed 3 years later when Elizabeth was 3 years old), was queen from 17 Nov 1558 until her death in 1603. Therefore, Elizabeth I was the reigning monarch from the time our dear Will was born until he was almost 40 years old.

Since Elizabeth died without an heir, the thrown passed to James I, great grandson of Henry VII and son of Mary, Queen of Scotts. He reined from 1603-1625, the last 13 years of Shakespeare’s life and work.

After Shakespeare died, James I was succeeded by his son, Charles I, who was deposed of his thrown, and his head (big event!), by the English Civil War in 1649. I can’t adequately express what strong shifts were occurring philosophically, spiritually, politically, etc. during this time.

A note on religion:

Joseph Pearce, in his 2008 book The Quest for Shakespeare: the Bard of Avon and the Church of Rome, has successfully laid out compelling evidence that Shakespeare was Catholic. (Phyllis Rackin briefly references scholarly arguments for Shakespeare having been brought up Catholic in her 2005 book Shakespeare & Women, just in case you wanted to hear it from a non-Catholic.) A brief summary of Pearce’s argument: In Elizabethan England, there were Catholics who had given up fighting to be Catholic, and there were Catholics still fighting to be Catholic. It is well documented that William was born and baptized into the latter type of Catholic family, to John and Mary Shakespeare. Additionally, during his life, Shakespeare is not registered in any of the parishes of the Church of England, he donated a portion of his property to Catholic priests in his will, he was friends with well-known Catholics (notably the martyred St. Robert Southwell, a poet priest), and in his will he left all his property to only one of his daughters (the one who had remained Catholic). Here’s an article by Joseph Pearce on the topic.

And if you care for my personal opinion, before knowing any of these arguments, when deeply immersed in reading Milton and Shakespeare in grad school, I penciled marginal notes all along Shakespeare, saying “This man is Catholic!” Chesterton anticipated this feeling when he wrote,

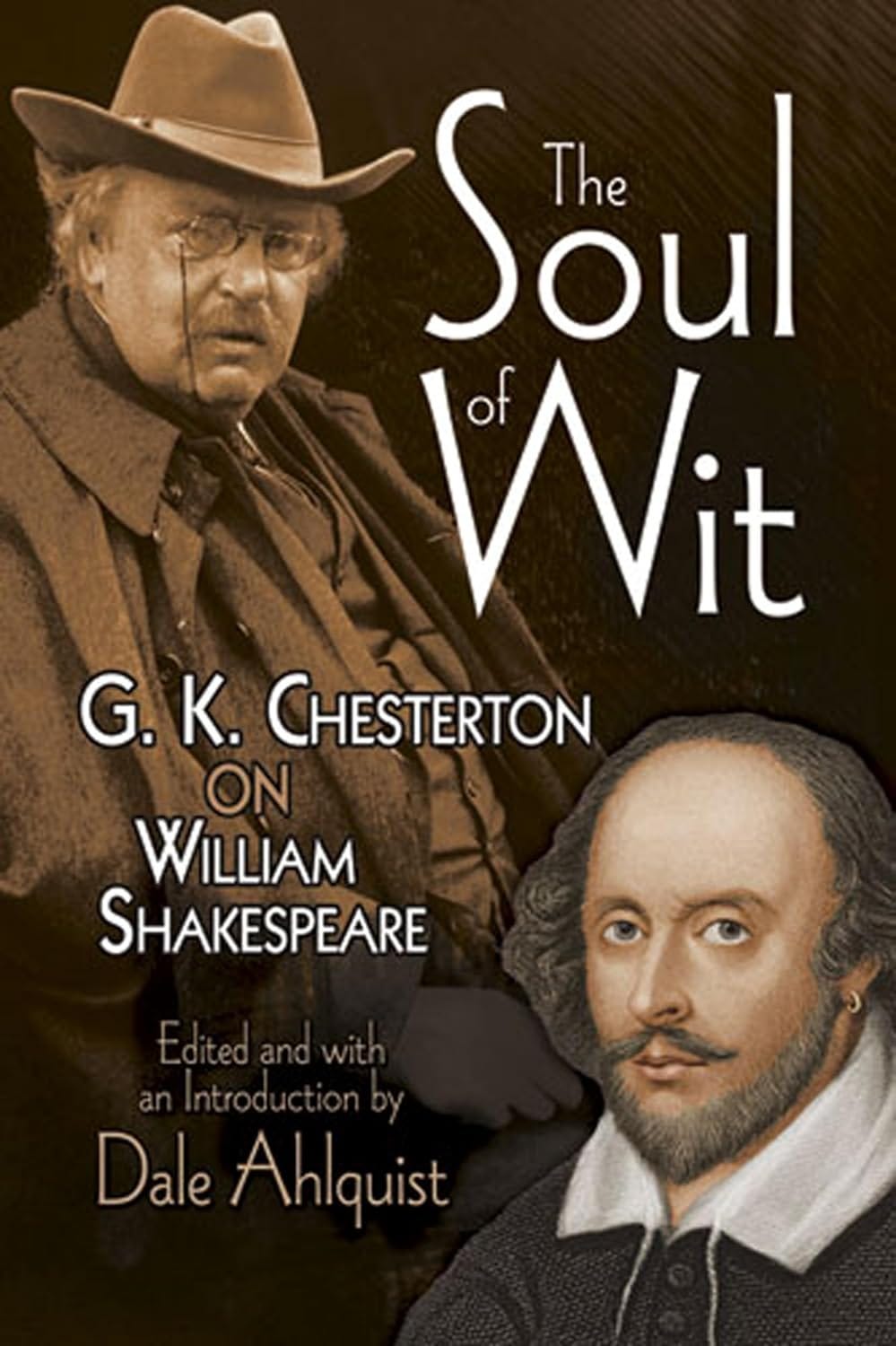

“Whenever Milton speaks of religion, it is Milton’s religion: the religion that Milton has made. Whenever Shakespeare speaks of religion (which is only seldom), it is of a religion that has made him,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

Why do I think this is relevant to mention? Because, we don’t have to leave our orthodoxy, or our Catholicism, at the door when reading Shakespeare. Meaning, when a suicide occurs, we can fairly well know what Shakespeare thought of suicide. When Hamlet’s father’s ghost appears, we can fairly well surmise that Shakespeare was imagining this apparition coming from Purgatory. Chesterton gets at this idea better,

“The old writers knew exactly what they thought about things, and then wrote about the things. They did not write with a moral purpose, but with a moral assumption. The author of Macbeth can sympathize with a murderer; but the whole play would be meaningless if there were a moral doubt about murder,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This is what I mean by not “checking your orthodoxy at the door.” Read, keeping in mind what is known to be right and wrong, and all is a lot clearer in Will’s plays.

Perhaps here it is well to note, along with Chesterton, that perhaps no one is misquoted as much as Shakespeare. Example: Perhaps you’ve seen engraved on a building, or made into a touching social media banner, “To Thine Own Self Be True.” –William Shakespeare; perhaps implying that Shakespeare was a rather trendy, moral relativist who would today say, “You do you.” While the quoted line does come from Hamlet, we do authors a disservice when we forget that they choose into whose mouths they put things. Meaning, when Shakespeare put the above quote into the mouth of the play’s fool, he was perhaps not intending people to take this as his own personal mantra – though I’m not sure he would’ve cared as much about this as I seem to, a word more on this below. :D

A note on seriousness (or not!):

G.K. Chesterton has been the most influential on my view of Shakespeare, and in the most pleasant of ways.

Chesterton contends that Shakespeare is one of the greatest authors of all time, AND that he is full of mirth, of ridiculousness, of laughter. That he is a “common man’s man,” much more instep with his Medieval predecessors than some of his Renaissance contemporaries. Therefore, while we should rightly stand in awe of Shakespeare as the greatest English author, we should also approach him as someone who wants to be approached. He was not trying to be a great man who spoke to only other great men, for the mark of a truly great man is his simplicity. As defense of this argument, note the simplicity of Christ’s fiction writing, of His parables. So, do not forget to look to laugh in Shakespeare.

“There is in Shakespeare something more godlike even than humor: something which the English call fun,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This may help us make sense of some of the more irreverent, or bawdy scenes. Shakespeare’s faith was strong enough to withstand humor.

“The moderns who disbelieve in Christianity treat it much more reverently than these Christians [referring to Medieval monks] who did believe in Christianity…I have seen a picture in which the seven-headed beast of the Apocalypse was included among the animals of Noah’s ark, and duly provided with a seven-headed wife to assist him in propagating that important race to be in time for the Apocalypse,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

A note on poetry:

“There is a sort of speech that is stronger than speech. Not merely smoother or sweeter or more melodious, or even more beautiful; but stronger. Words are jointed together like bones; they are mortared together like bricks; they are close and compact and resistant; whereas, in all common conversational speech, each sentence is falling to pieces,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

This quote, for me, summarizes why we read poetry, why we read Shakespeare, why we love to read good writing. Instead of remaining a critic on the outside saying, “That was ridiculous, no one talks like that,” after a long soliloquy by Romeo, or Othello, or Macbeth, or Hamlet, or any other long-winded person in book. Instead, to love literature is to open oneself up to the reality of how words should be, a glimpse at what words might have been if there hadn’t been a Fall, and how words are in Scripture, and how the Word is in Heaven. So, when we read Shakespeare (especially if we’ve already read a plot summary – more on this later), let us revel in the words, in how Shakespeare has someone say something, in the turn of phrase, or accurate description, or in the comedic or tragic timing.

“If Shakespeare were under the limitations of realism, he would be forced to make Macbeth express his depressions or despair by saying, ‘Blast it all!’ or ‘What a bore!’ And these ejaculations do not express it; that is part of the bore. But as Shakespeare had the liberty of a literary convention, he can make Macbeth say something that nobody in real life would say, but something that does express what somebody in real life would feel,” (G.K. Chesterton, The Soul of Wit).

A note on spoilers:

Be spoiled! Reading a summary before you read Shakespeare is highly helpful, and enriches, not detracts, from the pleasure of reading. Shakespeare often re-worked well-known plays, Much Ado About Nothing, is no exception. Therefore, most of his audience would have entered the theatre knowing what was going to happen, and therefore looking forward to how Shakespeare was going to make that happen. Would he alter some small or large part of the plot? Would he remove some details or add others, and thus change the entire message of the play? Would he go wild with his word-skill and phrase the whole story with such “sticky” language that one laughed, cried, and applauded at the same time?

Side note: I think a good example in current culture of how subsequent storytellers can play off of pervious storyteller’s works, is in the 2005 Pride and Prejudice movie. This most recent version could afford to move really fast, and not fully introduce characters, because it could safely assume most of its audience already knew the plot well enough to keep up. I noticed this aspect because my husband, not a big Austenite, was fairly lost throughout the whole thing. So, do yourself a favor, read a summary of the play before you read the play, then just sit back and enjoy the words.

A note (my last) on dialogue:

It’s because of Shakespeare’s mastery of dialogue, that I began to notice that some of my favorite authors were those who had mastered this craft, the craft of actually writing the quirky, disconnected, and eloquent ways of speech. L.M. Montgomery in her Anne of Green Gables series (March 2021), Harper Lee in To Kill A Mockingbird (May 2023), and Leo Tolstoy in Anna Karenina (February 2022), are a few examples I find of excellent dialogue contained in excellent storytelling. On the flipside, there are some books that I’ve found very interesting for the story, but which continued to lose me every time a character opened their mouth, because I kept finding myself thinking that: 1) that character wouldn’t actually say that, or 2) that’s just the author spewing their philosophy through the mouth of a character, or 3) the character didn’t need to say that, the author is just using the character as a lazy way of moving the plot forward2. Needless to say, looking closely at dialogue has made me realize just what a tricky art it is. And Shakespeare, arguably, does it best. Currently we say, “it all comes down to communication.” Well, that’s another way of saying, even in our daily interactions, dialoguing well is crucial. So why not read a man who mastered it in the written word?

(Now that you’ve read her beautiful writing, go follow

on her Substack so that you don’t miss any writing she does in the future!)Thanks again for to Jess for writing that up for us. I hope it helps you dive into the world of Shakespeare with more confidence and delight!

Another Book I’m Enjoying

I have had this book (Planet Narnia by Michael Ward) on my shelf for years and not gotten around to reading it. It seemed like it would be a good book to get to someday, but never now. However it has received so many glowing recommendations from people I trust (including Alan Jacobs) and I’m rereading the Narnia series aloud to my kids, that it seemed like a good time to at least skim through it. I have been so pleasantly surprised how much I’m enjoying it. It is well written, informative, and engaging. I am reading it very slowly, but every time I get a few pages read I feel more at home in the world of Lewis.

Other Things I’m Enjoying

This website detailed the Island Jolabokaflod (Book Flood) Tradition is delightful! It may be a little too late to start the tradition this year, but there is always next year! I will be personally be celebrating by reading way too many books at the same time during the 12 Days of Christmas!

A "Seed Catalogue" of Ideas for Simple Living…there is no way I will be able to live my life while checking all of these off, but there are some great ideas here and even simply reading the list and thinking through your routines is a humanizing exercise in itself!

I hope you all have a lovely last two days of Advent with your families. Next week I will be back with some reflections on my reading in 2023 and some favorite picks.

Until then, I wish you many pockets of time to cozy up with a good book!

“…the more you read, the more you understand about literature as a whole…”

-Northrop Frye, The Educated Imagination

A Few Reminders

Next up in January is Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare and then on to Middlemarch for February and March.

If you found your way here and are not part of an in person book club, welcome! We would love you to read along with us. But, in person literary community is a beautiful thing. So please contact me if you’d like to join or start a group!

If you are part of a group, but you’re not on our Slack page, please contact me. That is where people share thoughts and logistics for each in person group.

Book lists from previous years can be found here.

We are now on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (with links to Substack) in order to hopefully spread the reading life to more people...if you want to like or share with any friends that want to start their own groups (or follow along virtually) please do!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. The few cents(literally) earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) go toward the time and effort it takes to keep Literature Book Club running and I appreciate it!

I expound on why I like contextualizing an author in Why (I think) I Read

The book I have in mind in this reference, is the book I use as my example of a Bad Bad Book in The Good Good, the Good Bad, the Bad Good, and the Bad Bad.