The Moonstone Revisited: Section 2

1st Period: ch. 15 - 2nd Period: First Narrative, ch 5

Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

Hello, Readers!

As we dive into this week’s reading, I just need a moment to give a quick applause for Wilkie Collins. The emotional range of this section combined with his continued knack for characterization is simply brilliant, (and you’re not alone if you’re seeing a strong Dickensian influence in his style - I mean, the name Drusilla Clack certainly sounds like it belongs right up there with Betsey Trotwood, Wackford Squeers, and Lucretia Tox1 ).

In this second section we’re seeing lots of sub-plots unfold alongside the central mystery of the Diamond, and we’re getting to know our main and secondary characters much better.

Some Themes & Quotes

Who is Hiding?

From the beginning of the story, we’ve had our eye on Rosanna. Though she never seems to “fit in” with her fellow servants, only Betteredge has seen the inner turmoil that she carries. Her tragic death at the sands was clearly foreshadowed in chapter four:

“Something draws me to it [the shivering sands]…sometimes, Mr. Betteredge, I think that my grave is waiting for me here” (first period, ch 4, p. 37)

At this point we suspect, given Penelope’s assertion, that she took her life because of her heartbreak at remaining unnoticed by Franklin Blake, but we see in her early discussion with Betteredge that she has long suffered with loneliness and an “unquiet” mind, AND we know that she is in some way, shape, or form, involved in the disappearance of the Diamond.

After Betteredge’s quiet, fatherly care for Rosanna throughout Sergeant Cuff’s investigation, the “discovery” scene at the sands is raw and heartbreaking:

“The dumb trembling held me in its grip. I couldn’t feel the driving rain. I couldn’t see the rising tide. As in the vision of a dream, the poor lost creature came back before me. I saw her again as I had seen her in the past time…The horror of it struck me, in some unfathomable way, through my own child. My girl was just her age. My girl, tried as Rosanna was tried, might have lived that miserable life, and died this dreadful death” (first period, ch. 19, p. 202)

With Rosanna dies also the secret of her involvement with the disappearance of the Diamond, or so we think. We later learn of the letter left in the care of Limping Lucy, but are left in suspense as we await the return of Franklin Blake who alone can open the letter. (The suspense this creates is simply *chef’s kiss* superb.) Ultimately, while the reasoning behind Rosanna’s tragic death is complex, its connection to the Moonstone certainly recalls to our minds the ominous curse the Diamond is said to carry.

I am intrigued by the relationship between Betteredge and Sergeant Cuff. Before Sergeant Cuff leaves, he verbalizes his appreciation for Betteredge’s character:

“To say you are as transparent as a child, sir, is to pay the children a compliment which nine out of ten of them don’t deserve. There! There!” (first period, ch 22, p. 229)

I love this quote, because it gets at why we readers, too, appreciate Betteredge and are so drawn to his narrative voice. His simplicity, hilarious digressions, and honest self-deprecation make him one of the only characters that we see NOT hiding. Even when he is attempting to conceal out of concern for others (i.e failing to be fully forthcoming about Rosanna), he is incapable of carrying it off - Cuff sees right through him every time.

Among the biggest questions we are left with at the end of this section is: what is Rachel Verinder hiding? Her behavior after the disappearance seems inexplicable, and despite everyone’s best efforts, remains largely a mystery. Here’s what we know:

Rachel has cut ties with Franklin Blake

Rachel has asserted, early in the second period, that she knows the hand that took the Moonstone, and that she knows Godfrey Abelwhite to be innocent in the matter.

Finally, Rachel confesses to Godfrey that she loves another who she has found unworthy of her:

“Suppose you were in love with some other woman?…Suppose you discovered that woman to be utterly unworthy of you? Suppose you were quite convinced that it was a disgrace to you to waste another thought on her?”

And then,

“I will never see him - I don’t care what happens - I will never, never, never see him again!” (second period, first narrative, ch 5, p 303-304)

We clearly have Franklin Blake in our minds as Rachel’s unworthy attachment given what we have seen of them in the first period combined with Lady Verinder’s assertion that Rachel confessed that she had been formerly ready to accept his marriage proposal, but the source of the break between them remains unknown both to us and Franklin himself.

Miss Clack is another character who hides. First, she hides her gospel tracts, those “precious publications”, around her aunts house in the hopes of eliciting some kind of deathbed “conversion”:

“when I reflected on the true riches which I had scattered with such a lavish hand, from top to bottom of the house of my wealthy aunt — I declare I felt as free from all anxiety as if I had been a child again” (second period, first narrative, ch. 4, p. 293)

Then, we find Miss Clack herself physically hiding behind the curtain, serendipitously placed to hear the entirety of a private interview between Rachel and Godfrey…(anyone else seriously LOL at this scene?!):

“To show myself, after what I had heard, was impossible. To retreat — except into the fireplace — was equally out of the question. A martyrdom was before me. In justice to myself, I noiselessly arranged the curtains so that I could both see and hear. And then I met my martyrdom, with the spirit of a primitive Christian” (second period, first narrative, ch. 5, p. 300)

Finally, another hidden secret, that of Lady Verinder’s grave illness, comes to light with her death, and we end this section as we began: in chaos. Rachel, now an orphan, is reluctantly engaged to Godfrey, the whereabouts of Franklin Blake remain unknown, and we’re no closer to uncovering the secret of the Moonstone.

Who Can See/Judge Clearly?

We’ve seen lots of judgments being made in these chapters. How the cast of characters sees and responds to the people and circumstances coming up here is intriguing, and we’re left wondering who is seeing clearly.

Sergent Cuff has proven himself, at least to some degree, in this section. His suspicion surrounding Rosanna Spearman has come to fruition in that we don’t doubt by this point that she has had some involvement in the Diamond’s disappearance, however direct or indirect her involvement may have been.

The two predictions that Cuff made to Betteredge at the moment of his departure have also come true. These circumstances certainly warrant some level of trust in the sergeant, but we’re still left with uncertainty in the end of this section as to whether his primary judgement about the diamond: that Rachel herself is behind the disappearance and left with the diamond in her possession, will prove true.

Another character in whom we have found reliable judgment is Penelope. Penelope has always seen clearly where Rachel’s affections lie, and she is also a step ahead of Cuff, who can only attribute Rosanna’s death to the mystery of the Moonstone’s disappearance. Rachel has seen clearly that Rosanna’s death was rooted in her unrequited love for Franklin Blake (which is later confirmed by Limping Lucy).

The entirety of Miss Clack’s narrative is sprinkled with her own judgments against the various characters. While they provide some excellent comic relief, they also serve the purpose of shedding light on how much (or little) Miss Clack’s judgments are to be trusted. Betteredge himself left us with the following warning:

“I hear you are likely to be turned over to Miss Clack, after parting with me. In that case, just do me the favor of not believing a word she says, if she speaks of your humble servant” (first period, ch. 23, p. 242).

His warning, combined with our affection for Betteredge after journeying with him thus far in the narrative compels us to quick distrust of the lady that early on in her narrative refers to Betteredge as a:

“heathen old man..too long tolerated in my aunt’s family” (second period, first narrative, ch. 1, p. 253).

While by the end of this narrative Franklin Blake has largely disappeared from view, we find Godfrey Ablewhite coming to the fore. Godfrey’s trustworthiness seems to be the lingering question by the end of this narrative. Clearly Miss Clack sees him in angelic light (until his “fall” in chapter five of this section, that is), but Mr. Bruff introduces some doubt as to his trustworthiness in chapter three:

“Apperances are dead against him. He was in the house when the Diamond was lost. And he was the first person in the house to go to London afterwards. Those are ugly circumstances, ma’am, viewed by the light of later events” (second period, ch. 3, p. 282).

Here again we have the appearance vs. reality theme, and even given Rachel’s assertion that she knows Godfrey to be innocent of the theft of the diamond, we, like Mr. Bruff, are perhaps not quite convinced that he is to be trusted.

(Side note - was anyone else utterly annoyed by his proposal to Rachel in chapter five? This whole scene reminds me of Andy in season 9 of The Office trying to convince Erin to remain his girlfriend even though she doesn’t love him because it would make him happy…iykyk.)

Men vs. Women

One last theme that I couldn’t help but notice in this section is the comparison of men and women. There are a couple of hilarious Betteredge gems here (some of which might be offensive if said by anyone but dear, old Betteredge):

“When a woman wants me to do anything (my daughter, or not, it doesn’t matter), I always insist on knowing why. The oftener you make them rummage their own minds for a reason, the more manageable you will find them in all the relations of life. It isn’t their fault (poor wretches!) that they act first, and think afterwards; it’s the fault of the fools who humor them” (first period, ch 17, p. 187).

“Whenever a woman tries to put you out of temper, turn the tables, and put her out of temper instead. They are generally prepared for every effort you can make in your own defense, but that” (first period, ch 23, p. 236).

On a more serious note, this men vs. women theme comes into play in a significant way in the characterization of Rachel Verinder. Back in the first period, chapter eight, Betteredge says of Rachel:

“She was unlike most other girls of her age, in this - that she had ideas of her own, and was stiff-necked enough to set the fashions themselves at defiance, if the fashions didn’t suit her views. In trifles, this independence of hers was all well enough; but in matters of importance, it carried her too far. She judged for herself, as few women of twice her age judge in general…” (first period, ch.8, p. 72).

We’ve already seen Rachel’s stubbornness/independence on display in her refusal to disclose all she knows about the Moonstone, and I’m watching to see how this element of her character will continue to play out in the coming chapters. (Though interestingly, in the second period we do see not one but two examples of Rachel yielding in this tendency, both of them involving Godfrey.2)

One final point on this men vs. women theme. Note the way that Rachel rebukes Godfrey in chapter two:

“You live a great deal too much in the society of women. And you have contracted two very bad habits in consequence. You have learnt to talk nonsense seriously, and you have got into a way of telling fibs for the pleasure of telling them. You can’t go straight with your lady-worshippers. I mean to make you go straight with me” (second period, ch 2, p. 266).

Final Thoughts/Questions

WHAT HAPPENED BETWEEN FRANKLIN AND RACHEL!? Rachel’s confession to Godfrey about her “lost love” opens up so many questions and leaves us in a new kind of suspense. I’m anxious for Franklin to return to the stage and hopefully reveal some answers!

Having read this book before, it’s hard to know how much I’m “reading in” a distrust of certain characters…that said I won’t share much in that regard. I’ll just say that Collins, like his pal Dickens, is a great character artist. I’m very impressed with the way he draws the reader in to making some explicit and implicit assumptions surrounding the people coming in and out of this story. I guess what I’m trying to say is - pay attention to who you find yourself gravitating to or feeling uneasy about in the story.

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

On the Podcast:

ep. 44: Taylor Swift & The Art of Storytelling w/ Katie Marquette

ep. 47: Intro to The Moonstone w/

What We’re Reading Now/Next:

April

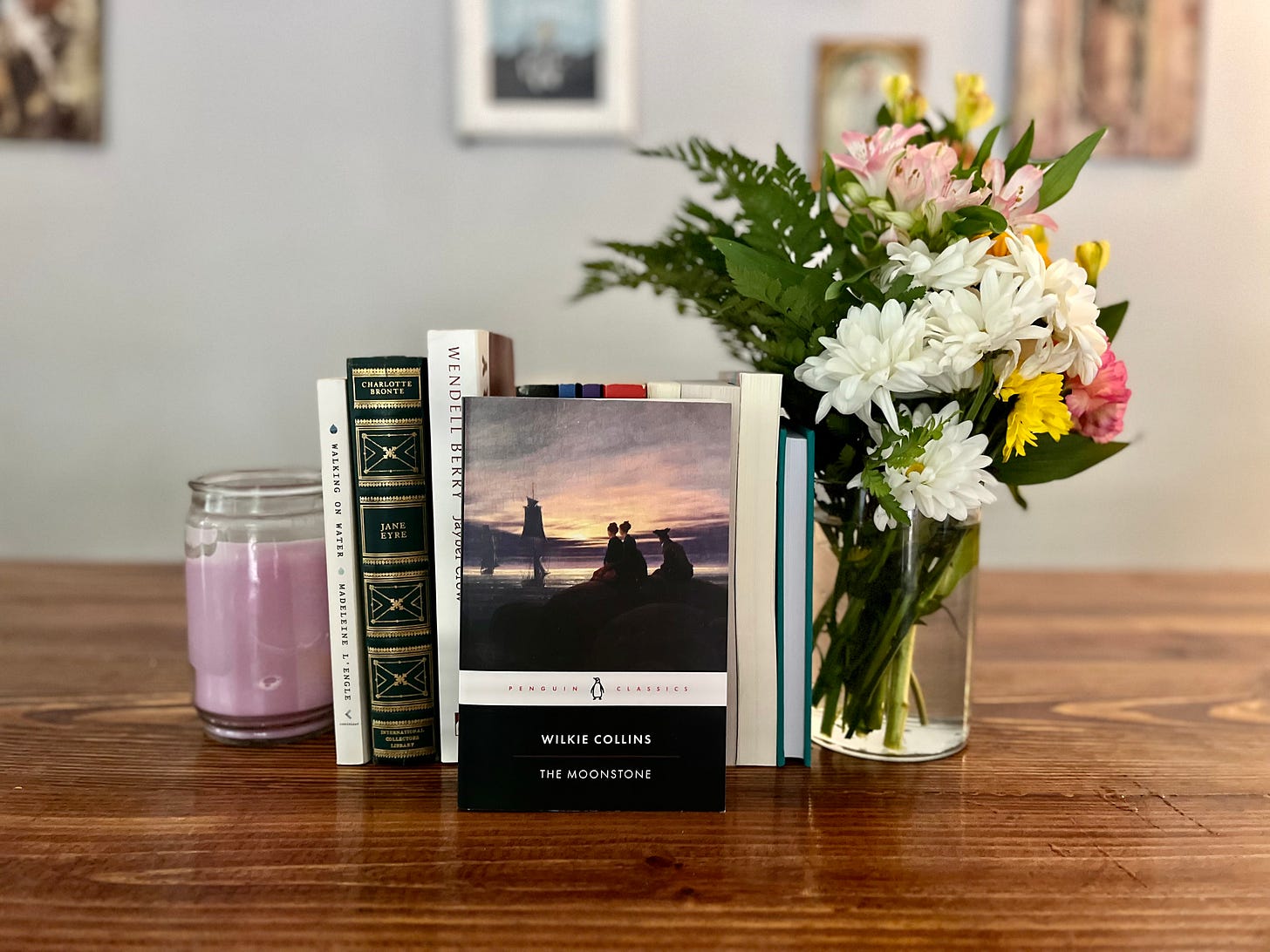

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

May

Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather

June

Trust by Hernan Diaz

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

We have turned on paid subscriptions which will allow you to support the work we are doing here as well as receive Read Along Guide PDFs each month, voice recordings of the Read Along Guides and Essays, and we are working on (printable) bookmarks for each book.

If you would like to make a small contribution to the work we’re doing here at Reading Revisited, we invite you to do so with the Buy (Us) a Coffee button below. We so appreciate your support!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, we appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running, and we appreciate it!

Reading Revisited is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Characters from Dickens’ novels David Copperfield, Nicholas Nickleby, and Dombey and Son, respectively.

I’m thinking here of her willingness to provide a written declaration of her knowledge of Godfrey’s innocence as regards the theft of the Moonstone - this is interesting despite her former insistence upon remaining utterly silent on the matter. Secondly, Rachel’s yielding to Godfrey’s proposal in chapter 5 despite her former objections.

This has been such a fun read so far. The theme of who can you trust/who judges correctly is one of the reasons I love epistolary novels so much, because it really gives the authors a wide playing field and a unique way to explore said theme. Clack was both hilarious and a bit sad as a narrator-because on the surface level worrying about a person’s soul/moral state, and having evangelizing zeal are all good things/things we as Christians ought to do. The problem is when we’re hypocritical pharisees and, alas, we don’t always have the wisdom to see that about ourselves!

Betteredge cracks me up. He's a delight to read. And Miss Clack behind the curtain!! I almost died of the hilarity, 😂 while also screaming, "Nooooooo!" about the proposal.