Laurels and Liberty

A first visit with Karen Ullo's latest novel: To Crown with Liberty

Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

This will not be about the Opening Ceremonies of the Olympics.

However, I am going to begin with what this post is not about because: first, it’s timely; second, it’s a way into discussing Karen Ullo’s brand-new book, To Crown with Liberty; and third, it’s a means of discussing the nuanced conversations, which Art, and specifically literature, can (and should) achieve.

Therefore, let us begin with the Olympic Opening Ceremonies.

Pictured above is the mascot for the 2024 Summer Olympics. NBC explains it thus:

“When French revolutionaries stormed the Bastille prison in July 1789, kicking off the French Revolution, they wore the caps, which have since been known as a symbol of liberty and the revolution.”

This bonnet rouge mascot, and especially its rather white-washed explanation, were a surprise to me. If I’d been in Paris seeing these little red hats parading around, I think I would’ve felt a bit like Viktor Krum at the Wesley wedding when he saw Luna Lovegood wearing the deathly hallows as a necklace bauble. And also, to quote Ullo’s narrator:

“Tricolor cockades abounded along with floppy liberty caps, which could never be called stylish whatever their symbolism” (197).

But I begin too critically, let me begin with joy.

In the last week of July, as athletes from around the world flowed through the heart of Paris, my smile filled with love for the Frenchness of the French.

As I watched the Opening Ceremonies dance along the shores of the Seine, over the Louvre, upon the scaffolding of Notre Dame, and across countless icons of Paris, I gave my mental voice a French accent, and said, “Here we are. We have no need to build anything new and vulgar. This is Paris.” I loved the pride imbibed by this nonchalance. I loved the old-worldly hauteur of a city which did not bow to creating something grand and large just to impress. Paris seemed to be saying to the world: We are Paris. That is enough to impress anyone. And if you are not, c’est la vie.

But my love for the French stumbled when this lady sang onto the screen.

I recoiled. Pride in a nation is good. Making a cartoonish operatic display of a deceased person? Not my idea of classy. And thus continued the clash of classy and odd; regal hauteur and dare-you-to-not-be-shocked hauteur.1

This unabashed glorification of the French Revolution unnerved me. Perhaps I’d forgotten some of my history and philosophy classes, in which the ideals of the French Revolution were the main source of discussion but not their actual results.

However, in more recent memory, I’d been reading A Tale of Two Cities (RR 2021), The Scarlet Pimpernel, and The Song at the Scaffold. And through each of these works ran a river of blood as surely as the Seine. Within the nuance of true Art, the philosophies of Parisian salons are shown to be able to become scythes, or, more accurately, the guillotine.2

Ideas are powerful. Ideas are great. Let’s talk ideas. But, let us not forget that they are a tool, which must be wielded well. For this reason, the French Revolution is of momentous importance to remember, but to completely glorify?

Additionally, the timing of my TBR pile and the recommendation of a friend were impeccable; during these Olympic Games I was simultaneously reading Karen Ullo’s third novel, To Crown with Liberty.

Published an excitingly recent 3-months ago, To Crown with Liberty thus wins the silver medal in the hottest-off-the-press competition in my reading life.3 This means that by writing this post, I have taken upon myself the strenuous—nay Olympic—challenge of reviewing a book without spoiling it.

Reviewing old books? That’s my forte. No spoilers possible. If you didn’t know Hamlet dies…well, he’s been dead over 400 years and it’s titled a tragedy...But reviewing a new work... Let’s just say, if my event is the 1600m, this paragraph is me warming up for the 100m.

I don’t want to spoil anything. I must not spoil anything. Especially since the entirety of this novel is driven by a burning desire to discover: what happened?!

So be patient with me fans, this long-distance runner is about to attempt to sprint through 300 pages, barely nodding at a few ideas as I pass them by.

The Plot

To contextualize this review, here is a plot summary that you can gain within the first 3 pages of the novel:

Narrated in the first-person by a young woman named Alix, this historic fiction novel begins in New Orleans in 1795. Alix is married to a gardener named Joseph, but her attire and the way other French immigrants react to her…

Then other voices raised a more familiar song.

Let us march, let us march until an impure blood waters our furrows…

Inside the tavern, three men dressed as sans-culottes, their heads adorned with bonnets rouges — those farcical crowns of liberty — raised their voices in the war cry of the Marseillaise.

“Hurry Alix.” Joseph sheltered me with his body, herding me away. For it was my blood they wanted. I had cast away my title, but my blood would always be my own.

“Hélas, is that ci-devant? Citoyens, look at that silk!”

…

Joseph’s fist collided with his jaw. “Get away from my wife, you swine!”

“Your wife!” the man laughed as he pulled a dagger from his boot. “You’re a laborer. This is…a marquise? A baronne?” The blade glinted in the twilight. “Don’t you wish to follow your queen, madame?” (12)

…reveal that in a former life, she was someone else, or at least, bore a different title.

If misfortune had stolen its glamour, at least its substance still remained (9).

From this initial chapter, Ullo sets the narrative’s pendulum swing in motion, moving backwards and forwards, alternating between Alix’s past life in France in the 1780’s and ‘90’s, and forward into the New World and a river journey further into it.

The narrative sustains its mysterious, unveiling nature almost until the very end, only providing the reader the last bit of past information in the second to last chapter.

Therefore, in order to not blemish your future, first-blush read, I have practiced extreme constraint (and extreme speed for a miler) and will only speak on three points: the French Revolution; Marie Antoinette; and slavery. I will finish with thoughts on: first impressions4 and how does one trust a new book?

Revolution

Like Charles Dickens, Baroness Orczy, Gertrud Von le Fort, and others, Ullo allows her novel to duly admire the philosophic seeds of the French (and American) Revolution.

“But this is a question of more than practicability. It is a question of who we are as the French people — whether we, who supported the Americans, who helped them gain freedom from tyranny, will nevertheless be tyrants ourselves. I claim no intimacy with Jefferson and Franklin,” he nodded to Lafayette, “but I have read their writings. ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal.’ That is the truth, the defending of which has caused our nation’s debts. And now are we to say to our people, ‘All men are created equal, but not subject to the same law’” (61).

The above scene takes place in Madame Necker’s famous, idea-refining salon. Thomas Jefferson, Bishop Talleyrand, Lafayette, Jacques Necker, Camille Desmoulins, Fréton, and other leading idealists of the day are given space within this work’s pages.

Personally, I enjoyed these intellectual interjects. In a necessarily emotional narrative, they were like solid objects floating on an ocean and onto which I could scramble for a rest (like Rose and Jack—RIP). Or (if you wish me to extend my running metaphor), providing the theories which led to the drama, was like providing quick, on-the-rocks sips of cognac amidst the heat and passion of the race, which temporarily quenched the drinker’s thirst, but ultimately derailed the whole event (…of the Revolution, not the novel).

But they always returned to greater questions, to the doctrines that governed mathematics. Words like rights and liberty flew like flags, decorated with quotes from Diderot and Franklin—entire worlds of thought into which I had never before entered.

…

As I drifted off, the evening’s conversation still flowed through me, a muddy river where I could not distill opinion from fact or truth from my own prejudices about the ones who spoke (62).

Alix’s last line, about the muddy river of opinions, facts, truth, and prejudice, understood in the context of her love for country and the men leading it, gives a glimpse into the nuance Ullo embraces and reveals through her fictional retelling of the French Revolution.

But the vaunted Peuple of the Revolution did not want careful nuance. They wanted submission (200).

Look at this subtle question we can ask ourselves because of Ullo: Yes, looking back we are able to see error in 1790’s France, but could this statement just as accurately apply to us and today?

Lest we be pastist (a new word I’m coining, it means: “to be biased against the past merely because those people or ideas are in the past.” Similar to how the word “sexist” means “to be biased against a person of the opposite sex merely because he/she is the opposite sex.” Surely a word with this definition already exists? Comment below and educate me.), every generation in every nation must acknowledge that we have the same potential for success or violence as previous generations. These events were not unique to France in 1792. We’re not off the hook. We’re not out of the race. We haven’t achieved some on-the-podium state where losing can no longer occur. We’re in the Games, we’re running the race, and, as Ole Ben Frank said, we gotta keep it. Or as good Paul said, we’re in it to win it.5

So dear people-of-the-world, the Opening Ceremonies… Can we, knowing our responsibility to promote and uphold ideas and events which lead Man towards greater goodness, can we, in all honesty to the carnage inflicted in the name of ideas and future peace, in the name of future equality and future stability, can we justify an un-nuanced celebration of the French Revolution? Do the ends justify the means? And, even if we subscribed to such a Machiavellian philosophy (or even, which is more likely, a utilitarian one), are the ends really so good that the means can be justified?

Back to Alix, let us let her remind us of the bloody turn, which the French Revolution took:

I heard them murmuring, late in the evening when they thought I was asleep, about mass graves and the sale of prisoners’ clothing, about cleaning up after Death. And then, I found I wanted to know. I begged them to bring me every paper, every pamphlet, every blasphemous, violent word, hoping that I might find some kernel of meaning. Yet there was no meaning - only logic.

…

The prisoners had been slaughtered for daring to exercise “the free communication of ideas and opinions,” without being “held innocent until they have been declared guilty.” The rights for which the delegates of the Third Estate had taken their oath in a tennis court three years before, the freedoms for which they resolved to stand against tyranny at the cost of their lives, had fallen to the swords of September like so many stalks before the scythe.

Reason and Rights, the twin gods of Enlightenment, had proven incompatible (276).

Place in front of your mind scenes from A Tale of Two Cities (not, unfortunately, from To Crown with Liberty, because to do so would reveal too much). Remember scenes of head-collecting women who knitted as lines of men, women, and children were guillotined into their laps. Remember how during the Reign of Terror, the streets of Paris literally ran with blood.

If we are to pay tribute to the French Revolution, surely some homage should be paid to the idea that Man must be encouraged to be good by social and legal means, else he can devolve into savagery.

Reason, untempered by love could justify even mass murder (287).

Ideas should be handled with great trepidation, with fear and trembling, awe and respect. I’ll press on, before I’m justly accused of forgoing the race in order to stand on a savon box.

One glorious Easter Sunday, I heard Bishop Jacques Fabre-Juene of Charleston, give an excellent homily on this Gospel reading:

On the first day of the week,

Mary of Magdala came to the tomb early in the morning,

while it was still dark,

and saw the stone removed from the tomb.

So she ran and went to Simon Peter

and to the other disciple whom Jesus loved, and told them,

“They have taken the Lord from the tomb,

and we don’t know where they put him.”

So Peter and the other disciple went out and came to the tomb.

They both ran, but the other disciple ran faster than Peter

and arrived at the tomb first;

he bent down and saw the burial cloths there, but did not go in.

When Simon Peter arrived after him,

he went into the tomb and saw the burial cloths there,

and the cloth that had covered his head,

not with the burial cloths but rolled up in a separate place.

Then the other disciple also went in,

the one who had arrived at the tomb first,

and he saw and believed.

For they did not yet understand the Scripture

that he had to rise from the dead.John 20:1-9 (emphasis mine)6

In his homily, Bishop Fabre focused our attention upon the old disciple (Peter) and the young disciple (John). He said (I paraphrase), that these two disciples are the model of the Church when she functions best. The youth of the Church run ahead with excitement and energy, flying towards new ideas and ways of implementing the Gospel in social initiatives and changes. And, Bishop Fabre said, this is good. But look, he said to us, look at how the young disciple waited for the old disciple. Look at how youth was respectfully patient, and allowed older heads the time they needed to catch up before they moved forward together, with the old leading the young. Bishop Fabre said that our Church (and therefore our world) needs both types of men: the young and the old; the excited and the cautious; the inventive and the traditional. It is only when we combine the power and speed of new ideas, with the steadiness and strength of old ideas, that we have a true force for good in the world.

The race of this world, then, might be seen as more of a relay than any individual event, with each athlete needing to wait on the previous to pass the baton. The French Revolution could have, perhaps, benefited from waiting on older minds.7 For as we know from the U.S. Men’s 4x100m, you can’t win if you failed to pass the stick. Too soon?

I’ll end this section with Ullo’s narrator, Alix, reflecting on how obsession with Revolution can become idolatrous:

Some of the rabble were singing Ça ira:

According to the maxims of the Gospel

The lawmakers shall accomplish all

The one who raises himself shall be humbled

The one who is humble shall be raised

The true catechism shall instruct us

And the terrible fanaticism shall be destroyed.

To be obedient to the law

Every Frenchman shall strive

Ah! Ça ira, Ça ira, Ça ira.

It’ll be fine.

I shuddered. To buy freedom with blood was a cause that could be justified; blood was a price that could bring martyrdom and redemption. But no constitution should ever have been bought at the price of idolatry (197-8).

Marie Antoinette

One small pleasure within this work, was how Ullo un-caricatured the “let them eat cake” version of Marie Antoinette, bringing her forward as a woman with flashing eyes, which “marked her as the daughter of an emperor” (174).

In a similar spirit, I set before you an un-cartooned image of Marie, with her head restored, her children by her side, and seated next to an empty basinet in memory of the premature daughter who died the year prior to this portrait.

Marie Antoinette de Lorraine-Habsburg, queen of France, and her children

by Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, 1787

Still pictured is her oldest son who would die the next year (and less than a month prior to the tennis court oath).

Below is a humanizingly poignant portrayal of that moment from Alix, as she watches Marie Antoinette watch her 7-year-old son painfully pass towards death:

I played Grétry, Mozart, Gossec, the greatest pieces in my repertoire, but I believe I could have played the simplest folk songs and had the same effect. While I played, the Dauphin lay silent, his breathing soft and sure. If I stopped, he groaned aloud, or raved as one gone mad.

The king came sometime in the afternoon, nodded to me, then took a seat beside his wife. He was so near-sighted, I doubt he ever realized who I was. He held Her Majesty’s hand while she held their son’s, and both of them—the greatest monarchs in the world—wept over their child (134).

To Ullo’s continued credit, she did not white-wash the King and Queen into innocent victims. As the ultimate leaders of France, she duly noted how their actions, too, played a part in the onslaught of anger and violence:

A monarch who would flee his own country could hardly be trusted to uphold its new constitution…Every prospect, every thought, swirled more dizzily than the last, the fragile strands of stability severed by a sentence: The king was gone (205).

Slavery

I should acknowledge, that if there was a literary tradition which the Ceremonies were directly referencing, it was not A Tale of Two Cities, or The Scarlet Pimpernel, or The Song at the Scaffold, it was Les Miserables.

Pictured above is the red-streamer bedecked Conciergerie, which was a major place of detention during the French Revolution, and also the prison where Marie Antoinette was held.

And I can’t argue with some epic singing of:

Do you hear the people sing?

Singing the song of angry men?

It is the music of the people

Who will not be slaves again!

When the beating of your heart

Echoes the beating of the drums

There is a life about to start

When tomorrow comes!

Speaking of all of us people who should all continually strive not to be slaves again, I found one of the most intellectually stimulating affects of interweaving the past and present of Alix’s life, and therefore the life of 18th century France and the life of 18th century America, was the conversation Ullo created, by this juxtaposition, on slavery.

Two-thirds of the way into the novel, one of the characters tells Alix that she is free to do what she wants because she “is not a slave.” Alix responds thus:

“Madame, I am less of a teacher—and more of a slave—than you know.”

She scoffed. “You’re no slave to anything but fear.”

I closed my eyes to shut away the sight of her scorn. It was too much like my own. “You’re right, madame. And fear is a brutal, unforgiving master” (213).

Slavery of the body is terrible. Slavery of the mind, of a person’s will, of a man’s ability to be a Man, much more so. This is why all attempts to free a person’s physical restraints, rightfully speaking, should merely be a step along the path to freeing the man’s ability to fully exercise his own will. Hence, the inclusion of the topic of education.

Alix’s extreme, deep discomfort (to say the least) with the institution of slavery as an idea, but even more so with the witness of actual enslaved persons, reaches a breaking point 50 pages from the end:

He let out a hiss. “Madame, have you ever owned a slave?”

“There are no slaves in France, monsieur.”

“Then I beg you not to interfere in what you do not know.” He stood.

…

“Monsieur…have you ever been held captive?”

He started. “What?”

…

Joseph knelt beside me. “If you want to tell him, I will stand by you. You should not hide, Alix. You should tell him who you are —and what you know that he never can.”

…

I stood and gestured to him to retake his seat on the log. “Please, monsieur. If you rest here with me, I will tell you about the true price of compassion” (256).

Without revealing the story, I cannot express to you the new perspective on what it means to be enslaved, which Ullo creates through the tool of her narrative structure. By the pendulum swing from past to present, France to Louisiana, Ullo presents a comparison of the hypocrisy of the French Revolution with the hypocrisy of the American Revolution, and—this is what adds to the power of her comparison—even while doing so, and specifically in doing so, is able to still uphold the good that was accomplished by both. The revolutionary ideas did spread freedom to many, if not to all. Ullo remains nuanced, through the end.

In addition to structure, the contemporary and modern feel of Ullo’s narrator’s voice, allows Alix a clarity of vision on slavery, which most of her actual contemporaries could not have had. To say this another way, due to the way this narrator speaks, I would have as easily believed she was born in the 20th century as in 1771. And I think this was incredibly helpful in Alix’s ability to speak against slavery. Her level of repugnance could only be written now, with a voice from today. Time is required to give Man a far-enough-removed vantage point from which we may see the cruelty of a past age. Cruelties of our own time are often too close to see. (God save us from the sins we inflict upon ourselves and others today, and, dear descendants, please forgive us.) Therefore, I found the modern voice of Alix to be a necessary device in order to allow her to see and expose evil for evil.8

Suddenly I knew why she [a slave] was bleeding. The dam of panic burst: inchoate rage, unbridled chaos rattling like sabers through my brain. I turned and stumbled back into the woods.

Joseph cried, “Alix! Alix, wait!”

…

I gasped when I could find the air. “It’s those poor people.”

Joseph looked back through the trees. His jaw grew rigid. “The slaves.” He put his arm around my shoulders. “I know you do not like it, but it will be like this everywhere we go. The only government that has outlawed slavery in the colonies is…”

“France.” I swallowed hard. “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.”

“For them, but not for you.” His eyes roamed over mine. “Do you want to go back to England? The United States? Spain, Portugal, Austria? I will take you anywhere. But I will not take you back to France to die.”

…

“Joseph, why do I see evil in this when no one else does?”

He kissed my hair. “Because you have seen so much more evil than they have. You recognize it now, no matter what disguise it wears.” He held me a moment longer. “Do you want to go back to Europe? You will not have to see slavery there.”

Alix…do not watch…

“No. Refusing to see it will not change what happens” (227).

Things I wish I could talk about:

There are so many aspects of this book, which I cannot reveal.

Therefore, here they will sit as a list of teasers: Abner, who he is, his Biblical namesake, and his passion; the snake bite in the garden; Joseph’s last name; what makes for justice and a good government; desire; the hunchback of Notre Dame; a comparison of fear in Von le Forte’s character Blanche and Ullo’s character Alix; “fathering a nation” (184) in Abner and Hamilton; the crowns of liberty; the role music plays throughout the narrative; the insane amount of research Ullo must have conducted; Fulton Sheen’s World’s First Love and how Woman sees “at a glance;” Alix’s mother, and how hierarchy creates the space for humility.

First Impressions & Narrative Voice

Now, I wish to (almost nearly) finish with my initial impressions of this book.

Dear Reader Dear Enthusiastic-spectator-in-the-stands-cheering-me-on-for-the-last-5-meters-of-a-very-slow-100-meter-dash, I admit that I may not have finished this book if it had not been recommended to me by a friend.

Why? Why might I have set this book aside? Why do I mention this? And how do we know that reading a new book will be worth our time? I will address this threefold question in order.

Why might I have set this book aside? 90 pages into this 313 page-work, I found myself thinking along these lines: Without knowing Ullo as an author (as I “know” Dickens, or Austen, or any other vetted-by-centuries author), I can’t know where she is taking the narrative. Without knowing the end of Alix’s story, I can’t know if the depth of her remorseful tone is appropriate. I’m worried this will merely be a sensationalized story without depth of insight. I’m worried this will be a lot of warmup exercises (high knees, butt kicks, and up-and-down the in-field karaokes—facing the same direction of course), but no actual race, no gun going off, no finish line, no head-thrown-back-arms-outstretched-exaltation.

Why do I mention this first impression? First, because if I acknowledge it, maybe you will not find it a stumbling block when you read this excellent novel; and second, because perhaps by acknowledging what I thought might have been a flaw, I will help you trust my opinion. (Why must we moderns appreciate criticalness as a mark of thought? I wish I could regain that innocence, which sees beauty first, and flaws almost never.)

How do we know reading a new book will be worth our time? The test of time is my favorite test. But, the race continues. And new heats continue to step up to the line. We can’t always use our favorite test.

Therefore, since the test of time is the conglomeration of many good men’s opinions, perhaps a good enough test for a new book is the good opinion of one man.

Therefore, I continued into Ullo’s narrative with good faith in my good friend. And I was rewarded.

I greatly enjoyed this book, especially in the latter half when Alix’s life began to take greater shape, and therefore I began to see larger themes. (I began to know that Ullo did have a finish line prepared for me.)

This appreciation then caused me to understand the fittingness of Alix’s narrative voice. I began to ask: If Alix had, instead, been remote, or overly-factual, would I not have thought her callous, or even heartless? And would that not have been an entirely different book? No, she had to be who she was to make this work what it is.

This book is good, and it needed Alix to be Alix.

Alongside Lewis’ The Great Divorce, I firmly hold that the ending of a work works its way retroactively back through the whole, re-coloring everything that came before it. This is why one can’t be sure if a book is good or not, until one has finished it.

Therefore, since I know the ending, and since new books require a trusted source to recommend them, this is me heartily recommending this book to you.

What a refreshing thing it is to read such a good story.

When you meet Alix, please squeeze her hand from me.

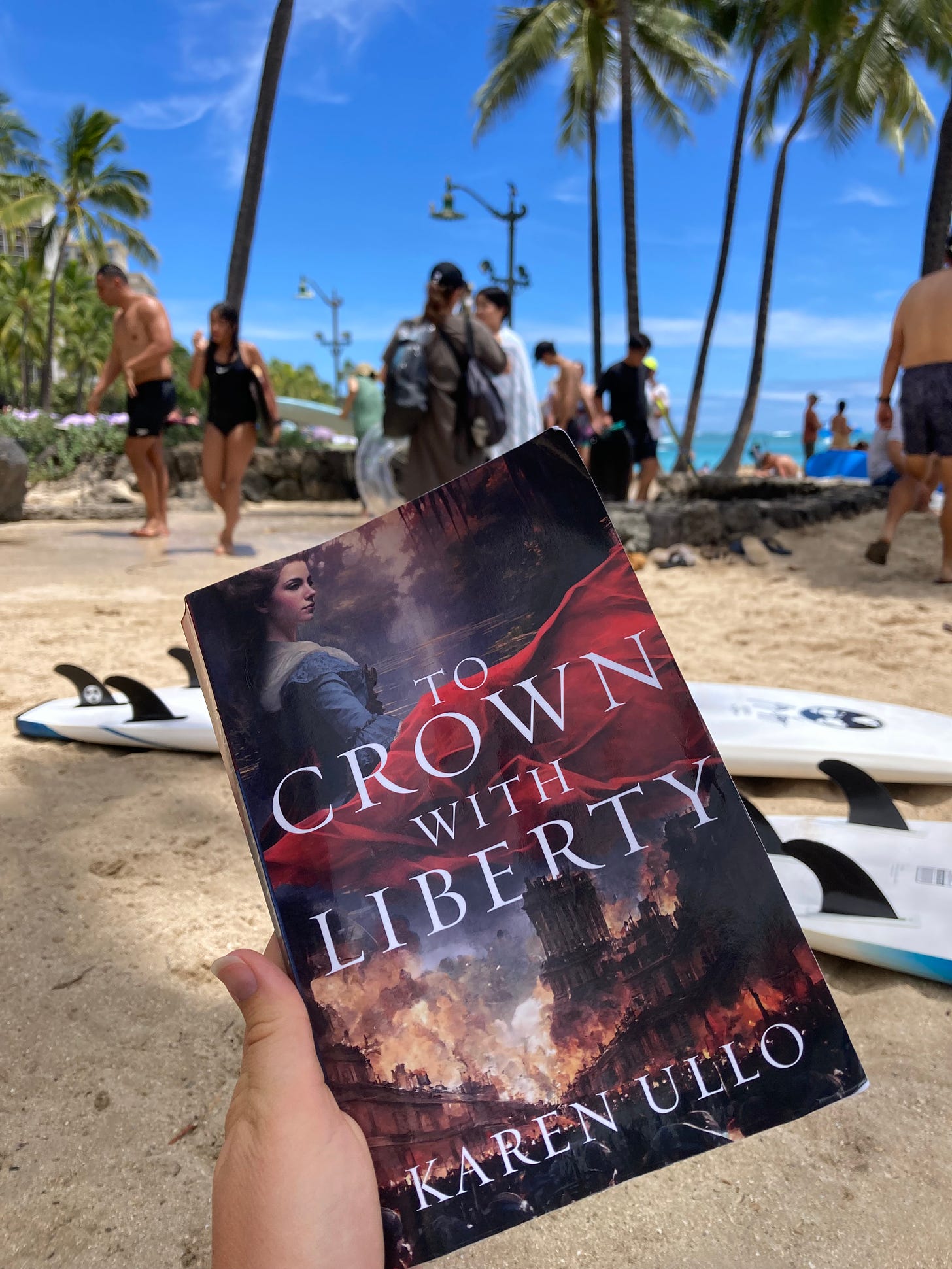

Summer Reading

To (nearly) end our very slow 100m dash with the jauntiest, most light-hearted stride possible…

…this was the perfect beach read.

Now please see Reading Revisited ep.6: Our Favorite Summer Reads to understand that I do emphatically reject the idea that being by water and sand means one should “indulge” in a “guilty pleasure” of idiotic trashiness.

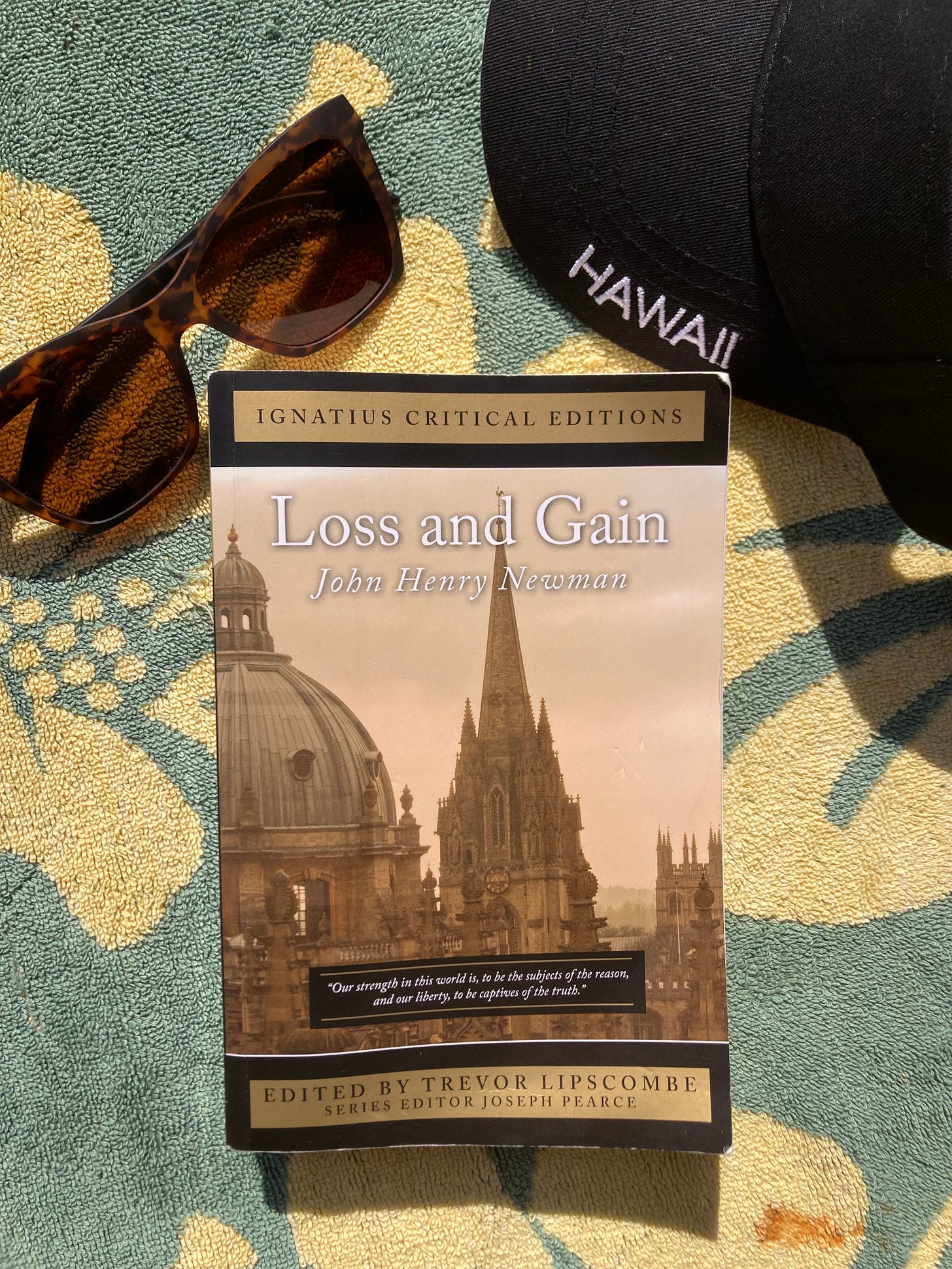

But, if you’re looking to take a break from being seemingly pretentious due to toting an Ignatius Press Critical Edition in your Bogg…

…than, Ullo’s plot-riveting novel is a gem to pull out, nod to the beach-towel-prone, sunburnt stranger next to you, and lift the book as if to say, “See, I can be one with the people.” Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, right my friend?

La Fin

Now to truly end.

(We’re crossing the finish line y’all, and my arms are thrown open wide in jubilation, as if I did not just clock in a 26-minute 100m…)

As we wrapped up the Olympics, I could not be more Team USA. Watching Simone Biles and Suni Lee; Gabby Thomas and the entirety of the women’s 4x400m team; and the men’s basketball star-studded lineup, I got that deep-seated yet light elation which only the Olympics brings. To see so many people who have worked, and striven, and sweat, and bled, and sacrificed so much with such focus and purpose…it makes one proud to be Man.

But as we crown these incredible athletes with laurels, and as we watch the little red caps dance around, it is perhaps well to remember, that true freedom, which is liberty par excellence, comes only from a crown of thorns.

No—most surprising was the wooden crucifix where an Indian Christ hung beneath a crown of black and white eagle feathers with the quill points tapered to look like thorns (290).

Stick!

Until then keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

Reading Revisited ep. 11: The Harry Potter Series with

Rachel Woodham

Pride and Prejudice Discussion Questions and Reading Guide PDF

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us! We have meetings in different parts of the country and over zoom each month. We would love to have you join us or start your own group!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, I appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running and I appreciate it!

As I said at the outset, this post is not about the Opening Ceremonies. However, I would be remiss not to at the very least acknowledge the heinous mockery which far exceeded a performance from a decapitated queen. I will let Archbishop Schnurr of Cincinnati and Bishop Cozzens of Crookston have the full say on this matter. You can read both of their short letters here. To quote Cozzens briefly, “France and the entire world are saved by the love poured out through the Mass, which came to us through the Last Supper.” Therefore, I will end this note with an echo of the dedication of To Crown with Liberty: “To the Holy September Martyrs, Pray for us.”

After its adoption, the guillotine remained France's standard method of execution until capital punishment was abolished in 1981. The last person to be executed in France by the guillotine was in 1977.

The gold-medalist in the hottest-off-the-press competition is the latter half of the Harry Potter series, since I read them within 24-hours of publication.

Word choice intentional. An homage to this month’s Pride & Prejudice was a must.

Points awarded to the reader who will put the un-“paraphrased” and non-colloquialized originals of these “quotes” and the actual names of their speakers into the comments. :D

Full readings can be found on the USCCB website.

“In a measure proposed by Maximilien Robespierre, the National Assembly had made themselves ineligible to hold office a second time and also barred refractory clergy from the elections. The original delegates to the Estates General, who had come from all classes of French society and represented the entire spectrum of French politics, were soon to be replaced by a body that would include only a handful of former noblemen and no one at all who spoke for the true Faith” (218).

Even as I say this, it would be stupidly blind of me not to acknowledge that the very century that I am saying “could not have seen slavery as clearly as modern-feeling-Alix,” is the very century at the tipping point of the global abolishment of slavery. Slavery existed in all places at all times and upon every people since recorded human history until the 19th century. It was the people of Christian Western Civilization that began to work towards its eradication. Surely I would be naive and small-minded to suggest that the people of Alix’s century should not be given credit for beginning to recognize and take concrete actions against an evil so pervasive. For an excellent study on this topic, see Thomas Sowell’s book.

Adding to my “to read” pile