Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

(the above are PDFs of all of the posts in this series…they are formatted to be printed as booklets and I hope it keeps you closer to your books and maybe a little further from your phone or computer. Let me know if there are any formatting issues to fix. I hope these are a blessing to some of you.)

Hello Reading Friends,

I hope everyone is settling into their back to school/beginning of Fall rhythms. I am very much appreciating all of this open window weather we are having even in the south. There is something so relaxing about open windows and sweaters in the morning. I am very much looking forward to some cozy Fall reading with some hot drinks, lit candles, and soft blankets.

I have already rung in the Autumn by finishing my first Gothic novel of the season, A Bloody Habit by Eleanor Bourg Nicholson (who is going to be on the podcast in a few weeks to introduce us to Gothic literature and Charlotte Bronte before we read Jane Eyre) and it was very fun. I highly recommend reading Nicholson if you haven’t yet.

We are also going to be talking about our favorite Autumn reads on the podcast in a few weeks so tune in there if you need some recommendations.

Now that we are finished with our short stories and L’Engle we are jumping into Jane Eyre next, so make sure you get your copy ready.

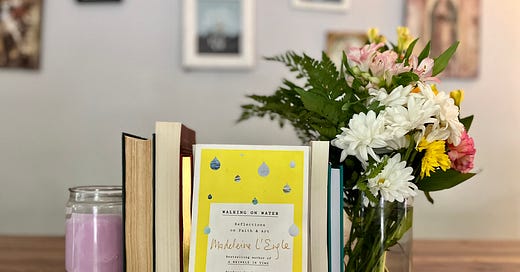

will be posting the reading schedule for that in a few days and then she will lead us through the book over the next month. I cannot wait to revisit a favorite book of mine with you all.Now let’s jump into L’Engle. I hope that this read of Walking on Water has been fruitful to your reading life and your faith life (and maybe even your artistic life). I know that even when I disagree with Madeleine, she gives me a lot to think about and I enjoy it each time I revisit this book. I am looking forward to our in person and virtual book club meetings because I think we will have a lot to chat about (as we always do) and maybe we can dig deeper into what we believe is the relationship between faith and art.

Madeleine, as always, touches on so many interesting points in these chapters, some that I agree with more and some less so. As I cannot touch on everything I will pick a few ideas from each chapter and share some quotes and thoughts with you. If I don’t touch on anything that you found meaningful, please make a list and come to book club ready to chat.

DO WE WANT THE CHILDREN TO SEE IT?

The title of this chapter comes from a story she tells about why her husband turned down the lead role in a racy play. He said, “do we want the children to see it?” She then connects this to the choices we make in our lives. I like this little WWJD motto so I will keep it in mind.

Madeleine starts off by revisiting the idea that the good artist is good regardless of his beliefs. She quotes her friend saying…

When your car breaks down, you don’t ask if the mechanic is an Episcopalian. You want to know how much he knows about cars.

-Canon Tallis

At first glance I agree with this quote and see the point she is trying to make about artists. However she then brings up other examples, like doctors, and I start to question if I agree. In theory I want the best doctor doing life saving surgery on my children or husband (or myself for that matter). But there are other issues where I actually am interested in what my doctor believes. If medicine were pure and I knew what was taught in medical school was pure fact, then of course. But, I have personally encountered that there are political and social agendas even in the scientific/medical world. Though if the doctor is truly committed to understanding the world in conformation with reality then he or she would be a good doctor regardless of other beliefs. But that is hard to know because you don’t usually read all of your doctor’s research papers before going in for a sick visit. Of course, bad science won’t work, but why would I (or my children) want to be the lab rat? So for now my mechanic can be whatever religion he wants, but I might ask a few more questions of my doctor.

I will be mulling over how this affects my view of the artist. This will be a great discussion at all of our book clubs I am sure. I truly believe the work stands on its own, but if you haven’t encountered the whole work how do you know? Are there artists who you trust their work despite their immoral lives or lack of faith?

She goes on to describe a situation she had in a writing class where she wrote a completely true story and the teacher said, “I don’t believe it.” She quibbled that it wasn’t even fiction. And he said,

If I don’t believe it, it isn’t true.

This sounds so relativistic if taken out of context, but I would like to defend the statement. In a work of art the artist is not singularly involved, the reader/viewer is as well. If what the artist creates is to be true, then it must be communicated in a way that the reader/viewer will understand it. This reminds me of…

When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs as you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock, to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind, you draw large and startling figures.

-Flannery O’Connor (Mystery and Manners, RR 2021)

Madeleine goes on to say,

If the reader can’t participate in that truth, then I have failed.

The role of the artist is not only to see, but also to make the reader see. I don’t think that is something most of us can do. It takes a lot of clarity of sight to not only see the world rightly, but to be able to communicate it clearly with the general public (whether they share your views or not). But then she goes on to say that even our participation in others’ art can help us be more human.

I am made more free by my participation in the work of other artists, especially the giants. And it is the other artists that teach the rest of us, offering their vision of truth….And if this vision is true, how can it conflict with the truth which Christ told us to know?

Art cuts across all denominational barriers…sign and symbol, sacrament and myth, metaphor and simile, are essential to al art, regardless of the personal belief or lack of belief of the artist.

This reminds me of Northrop Frye (a favorite literary critic of Angelina Stanford, from The Literary Life Podcast) and how he talks about the universality of symbols…

The imaginative is not a matter of making things up in a vacuum but of transforming reality in a way that reveals deeper understandings of life.

-Northrop Frye (The Educated Imagination)

To bring this chapter to a close I want to quickly touch on the connection Madeleine draws between prayer and the work of the artist. This connection reminds me of the connection that Simone Weil makes between academic study and prayer. (But actually maybe go read the essay linked below real quick…it might be just the thing you need to read to start off the school year.)

The key to a Christian conception of studies is the realization that prayer consists of attention. It is the orientation of all the attention of which the soul is capable toward God. The quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.

-Simone Weil (Reflections on the Right 'Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God)

I really like the idea that we all have a point of view, but that “God has a view” and that this is where stories can bring us closer to objectivity and seeing with God’s eyes. Where else can we live behind multiple people’s eyes and see the world in a different way than our real life would allow?

L’Engle wraps up the chapter with a story about her granddaughter being injured and it illustrates the discipline of prayer she has emphasized earlier and the idea that love/relationship come with vulnerability, but they are more than worth it.

All shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well. No matter what. That, I think, is the affirmation behind all art which can be called Christian. That is what brings cosmos out of chaos.

THE JOURNEY HOMEWARD

…the chief difference between the Christian and the secular artist—the purpose of the work, be it story or music or painting, is to further the coming of the kingdom, to make us aware of our status as children of God, and to turn our feet toward home.

L’Engle claims that artists and see and inspire awe of God like the Scriptures, and better than the churches do. I can definitely sympathize with this in reality. I do not think this necessarily has to be true and I have been part of church services and liturgies where I have been inspired by awe for God. But I do think art and stories can draw me closer to God and allow me to see the awe through the mundane at church.

I enjoy Madeleine’s use of paradox. It helps me to see and experience the reality that most of life is filled with nuance and the both/and that is so present in truth. I specifically appreciate the paradox and balance that is the ability to abandon oneself to the work of art while also maintaining steady discipline and habit. It seems so contradictory, but the more I think about it the more it makes sense. How can inspiration ever strike if I am not habitually present to receive it?

In prayer, in the creative process, these two parts of ourselves, the mind and the heart, the intellect and the intuition , the conscious and the subconscious mind, stop fighting each other and collaborate.

I will end this chapter meditation with some of Madeleine’s musings on the mother artist, which I think we can all appreciate even if you don’t personally consider yourself an artist.

For a woman who has chosen family as well as work, there’s never time, and yet somehow time is given to us….A certain amount of stubbornness—pigheadedness—is essential.

I am actually sitting her typing away on computer as a very sweet, yet incredibly aggressive, two year old is actively closing my computer on my hands. Which is to say, I feel Madeleine on this. There is never time, yet the desire to create is there and, as L’Engle reminds us again and again, to participate in creation even in a small way is participating with our creator and makes us more human. So I encourage everyone to take the time you don’t seem to have and try anyway. Even if your version of creating is participating with the author in the reading of a book (that is my preferred way of participating most days).

I had to learn that I was a better mother and wife when I was working than when I was not.

I could go on, yet I must move on so I will leave you with a few more quick points from this chapter: an artist must have order (which must be another cause of frustration to the mother artist), work shouldn’t be a drudgery (look to the children for inspiration), most artists don’t create in ideal lives but in the margins (an encouragement and conviction to us all…as I was writing this I got pulled into 30 minutes of neighborhood drama…we must create even when the time is short), and finally, L’Engles writing style reminds me of the Count from A Gentleman in Moscow (RR 2023).

THE OTHER SIDE OF SILENCE

It is a humbling and exciting thing to know that my work knows more than I do.

This is an idea that I simply love (and have probably attempted to wax eloquent on it far too many times, so forgive me and indulge me one more time). The artist must to the work and show up to listen and then finally create, however there will be truth in the work that even the author didn’t intend (if it is a true work of art). That is an amazing thought. If we truly believe that we are creating under a providential God, then of course he can put things into the work that even we don’t intend or understand.

I am not sure about this whole idea that higher math is easier than lower math, maybe I have never reached high enough in math to know, but I am interested in the idea that math could open up theology to us in a new way. It makes sense. If we believe in natural law, then of course all truth relates to each other and can never contradict itself.

It is nothing short of miraculous that I am so often given, during the composition of a story, just what I need at the very moment that I need it.

I was reminded of

’s idea of The Providential Bookshelf when I read this quote from L’Engle. If books tend to find us exactly when we need them then of course ideas can too. I am going to keep this close to my heart and meditate upon it in seasons of discouragement when the ideas don’t seem to be flowing to my tired mind.Perhaps art is seeing the obvious in such a new light that the old becomes new.

I appreciated the image of book writing that L’Engle leaves us with toward the end of this chapter…

When I start writing a book, which is usually several years and several books before I start to write it, I am somewhat like a French peasant cook. There are several pots on the back of the stove, and as I go by during the day’s work, I drop a carrot in one, an onion in another, a chunk of meat in another. When it comes time to prepare the meal, I take the pot which is most nearly full and bring it to the front of the stove.

I have the habit of having far more seeds of ideas for essays than I have time to write. So I periodically think of an essay title, make a draft with only the title, and then let it sit there for months. One day I’m sure I will bring a few of these “pots” toward the front of the stove, but right now they are back there simmering. I’m very thankful for this image.

I will end this chapter’s musings with this quote that I think exemplifies what L’Engle is doing in this book, but also what we are doing when we read and talk about this book…

In trying to share what I believe, I am helped to discover what I do, in fact, believe, which is often more than I realize. I am given hope that I will remember how to walk across the water.

FEEDING THE LAKE

Alright, let’s wrap this post and this book up!

We all feed the lake. That is what is important. It is a corporate act.

This chapter title comes from the idea that there is a lake of creativity and that anyone participating at any level of creation is “feeding the lake” as it were. The “giants” have larger streams and rivers, but even small acts of creation are contributing as well.

I love; therefore I am vulnerable. When we were children, we used to think that when we were grown we would no longer be vulnerable. But to grow up is to accept vulnerability.

This reminds me of…

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.

-C.S. Lewis (The Four Loves)

L’Engle also visits this theme a lot in her fiction. The end of A Wrinkle in Time is a great example of this. It seems so simple, but it is something I need to be reminded of often in mothering.

The way L’Engle talks about the church makes me think that she doesn’t have a good understanding of development of doctrine, which is the idea that doctrine does not contradict itself, but it can develop to account for the increase in knowledge we find in all disciplines, including science. Because we believe in a God of order who created an ordered universe, we can know that true knowledge will never contradict with faith. Some quotes make me think L’Engle knows that herself, but isn’t aware that the institutional church does as well.

Why should there be a conflict? All that the new discoveries of science can do is to enlarge our knowledge of the magnitude and glory of God’s creation.

And I will end where Madeleine leaves us, contemplating life and death, the Incarnation and the Resurrection.

But only if I die first, only if I am willing to die. I am mortal, flawed, trapped in my own skin, my own barely used brain, I do not understand this death, but I am learning to trust it. Only through this death can come the glory of resurrection; only through this death can come birth.

And I cannot do it myself. It is not easy to think of any kind of death as a gift, but it is prefigured for us in the mighty acts of Creation and Incarnation; in Crucifixion and Resurrection.

And there we have it, we have finished our yearly Book about Books. I hope that you have enjoyed contemplating the connection between faith and art, truth and beauty, and the mystery of creation. I am eagerly awaiting the chance to talk to some of you at our in person and virtual book clubs and I hope the rest of you have great conversations as well.

*I am not going to leave you with discussion questions because there are many in the back of the book. But, please, if I missed anything you were hoping to touch on (which I’m sure I did) bring it to your book club. The in person conversations are where the connections between people and ideas are made the best.

Now I hand you off to the lovely

, our resident Short Story Enthusiast to chat about First Confession by Frank O’Connor…First Confession

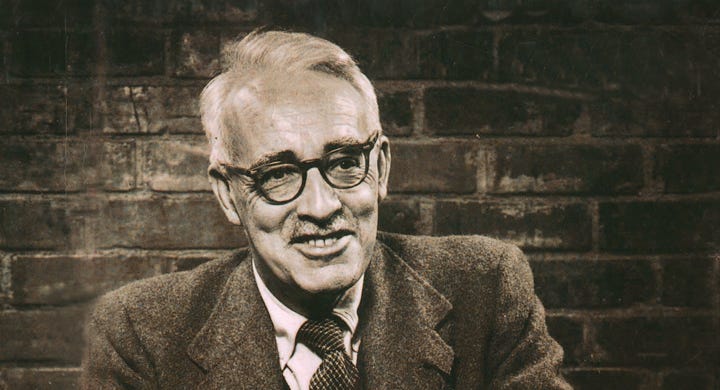

I am so very excited to introduce you to one of my favorite masters of the short story form: Frank O’Connor. Though I have read relatively few of his over 150 short stories, the ones I have read have etched characters into my consciousness with a vividness and permanence entirely disproportional to the brief time I have spent with them. Some great writers are great because they have mastered the craft of constructing stories with memorable and riveting plots, some because they capably string together beautiful sentences into well-designed paragraphs, some because of their poetic and evocative imagery. Frank O’Connor for his part was an absolute master of characterization. “First Confession” is six pages long. Yet Jackie, Nora, Ryan, and the unnamed priest are all well developed and completely believable characters; Jackie’s voice, the voice of a seven year old boy, brings power and force to the story precisely by being perfectly accurate. But who was O’Connor? And how did he develop this talent for characterization?

Frank O’Connor was born in Cork, Ireland in 1903 (making him a close contemporary of L’Engle (1918-2007), Graham Greene (1904-1991), and Caryll Houselander (1901-1954)). His given name was Michael Francis O’Donovan, which always makes me laugh a bit because it seems so similar to his pseudonym. Being as he is an artist, it is perhaps unsurprising that Frank’s childhood was less than idyllic. His father, Michael O’Donovan, was an alcoholic whose debt, struggles to provide for his family, and abuse of his wife and son created a harsh home life. Frank’s mother, Minnie O’Donovan, was a strong and resourceful provider, and her perseverance in the face of domestic injustice greatly inspired Frank. Like L’Engle, Greene, and Houselander, O’Connor’s childhood experiences of suffering profoundly affected both his theology and his art, which frequently deals with family conflict and personal hardship.

Like many Irishmen of his time, O’Connor became involved with the Irish nationalist movement as a teen. He developed a strong sense of patriotism, desired to see Ireland free from British rule, and joined the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence. In 1923, O’Connor was incarcerated for his political beliefs. During his imprisonment he read and wrote extensively, and became disillusioned with political action as a means of effecting change in society. He determined instead to change society by changing the culture. Accordingly, he began publishing short stories, poems, and essays, often drawing on his personal experiences of Catholicism, rural Ireland, family life, war, and poverty to create powerful works of literature.

By the 1940s, O’Connor was internationally recognized for his skill. He traveled extensively as a lecturer before settling for many years in America as a professor at Harvard and Stanford. While his literary career was fairly stable, O’Connor struggled to maintain his romantic relationships. His first marriage ended in divorce after fourteen years and three children, and was followed by a romantic entanglement and a son, and then by a second marriage and another daughter. A Catholic from birth, O’Connor remained a Catholic until his death in 1966. While at Stanford, he overlapped with Wallace Stegner (Crossing to Safety (May, 2024)), who would write a tribute upon Frank’s death called "Professor O'Connor at Stanford.” Sadly this does not seem to be available online!

Frank O’Connor’s work shows a deep understanding of the cultural and spiritual significance of Catholicism in Ireland. Yet, despite his loyalty to and love of the Church, he was not afraid of criticizing aspects of Catholicism as he experienced it in Ireland. His stories often highlight the dissonance between the abstract beauty of an ideal and the ugliness of its implementation by fallen people. He applied this lens equally to family dynamics, Irish nationalism, and Catholic doctrine. For example, in “First Confession”, the beauty of confession is overshadowed at first by Ryan’s obsession with guilt and hell, Nora’s hypocrisy, and the priest’s initial anger.

Speaking of, let’s take a deeper look at “First Confession!” This is definitely one of O’Connor’s more humorous works, and it never fails to make me smile.

The story explores the theme of appearance vs. reality in Jackie’s family life, his moral life, and his experience of Catholicism. While Nora frequently appears outwardly pious, she is spiteful and conniving toward Jackie. Her affected piety contrasts with Jackie’s apparent naughtiness, but lack of genuine malice. The children’s catechist Ryan appears holy as well, yet she

came every day to school at three o’clock when we should have been going home, and talked to us of hell. She may have mentioned the other place as well, but that could only have been by accident, for hell had the first place in her heart.

Her obsession with hell and damnation instills fear rather than hope or joy in the young children she prepares for confession, and her lack of balance calls the reality of her holiness into question. Finally, the priest appears angry at first, initially infuriated by Jackie’s mishap in the confessional, but his willingness to reassess the necessary balance of justice and mercy needed to minister to Jackie shows that he genuinely cares about his flock.

I love this priest. For his ability to deadpan during a seven year old’s first confession:

“And what would you do with the body?” he asked with great interest?

“I was thinking I could chop it up and carry it away in a barrow I have,” I said.

“Begor, Jackie,” he said, “do you know you are a terrible child?”

but even more because he is the foil to O’Connor’s critique of Catholicism within the story. O’Connor often struggled to reconcile his experiences of the Church as a source of guilt and fear with his knowledge of the Church as a source of cultural, moral, and spiritual beauty. We see O’Connor’s real frustration with the Church through his portrayal of Ryan, as he observes that religion should not be about meeting obligations out of guilt or fear, but rather about growing in relationship with Christ, and through Christ with each other. The priest models this by taking the time to build a relationship with Jackie, who accordingly comes to experience the joy of the sacrament and overcome his terror of confession. It is notable that the priest is not given a name when all other “speaking roles” are. This seems to highlight his role as being representative of all priests.

I truly respect O’Connor’s ability to offer on the nose critiques of institutions that he loves from within those very institutions. His criticisms of Irish nationalism come from an unwavering patriot’s heart, and his criticisms of Catholicism are balanced with examples of its efficacy, and nuanced by his own faithfulness. Through the priest in “First Confession,” O’Connor challenges his readers to reconcile justice and mercy, fear and joy, and appearance and reality in their own conception of the Church and her sacraments.

If you are interested in reading more of O’Connor’s work, much of it is available for free online! If you want to appreciate O’Connor’s range and don’t mind something significantly darker, “Guests of the Nation” is well worth the read. One of his most famous stories, “Guests of the Nation” explores the moral no-man's-land found when duty to friends and duty to country directly conflict. If you are in the mood for another humorous read from a child’s perspective, “My Oedipus Complex” is absolutely hysterical. Narrated by five year old Larry, the reader experiences the jealousy of a child learning to “share” his mother with a father newly returned from war. As in “First Confession” the narrative voice is spot-on, lending humor and power to the work.

Thanks again to Sarah Van Hecke for that reflection on our final short story! That is all we have for now. I definitely encourage you to read the short story, read Sarah’s reflection and questions, and then read the story again. Revisiting each story will give deeper insights and, I think, lead to great discussion in a few weeks! Here are the links to the past posts if you missed them (or scroll up for those PDFs to print):

August 21- Introduction to Walking on Water and each short story

August 28- Waking on Water Ch. 1-4 (pgs 1-68) and The Hint of an Explanation by Graham Greene

September 4- Walking on Water Ch. 5-8 (pgs 69-135) and The Father by Caryll Houselander

September 11- Walking on Water Ch. 9-12 (pgs 136-190) and First Confession by Frank O’Connor (you are here)

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

RR ep. 14: How to Fight Against Book Gluttony w/ Autumn Kern

Reading Revisited ep. 13: Intro to Madeleine L'Engle with Katie Marquette

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, I appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running and I appreciate it!

Yes, lots of fodder for conversation here! Has the date for the online conversation been chosen? Maybe I don’t know where to look…Forgive me!