Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

Hello Fellow Readers,

I come to you from the chaos that is back to school week. We started school today (Tuesday) and so did my school teacher/grad student husband. So needless to say, it is a bit hectic around here. It is lovely to be getting back into the normal routine, but that always comes with the process of figuring out all the kinks in the new schedule. You know when you need to find a hole in something? You fill whatever it is with water and when the water drips out, you know where the hole is. My husband likes to say that the role of the toddler is to be the water that leaks from the holes of all my well laid plans. I will just say, the toddlers fulfilled their role to perfection. But as is the homeschool life with so many kids, always an adventure.

I always come to the Fall with an eagerness to get back to a lot of routines, but one aspect I am especially excited to return to are my reading routines. I won’t go into too much detail here because we are going to have a discussion about wrapping summer reading and plans for the Fall on the podcast next week, but I am enjoying kicking off my Fall reading life with this lovely book about books. Nothing can spark my love of reading (and life in general) as L’Engle talking about the wonder of story and words and reality.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, make sure not the miss the latest podcast episode where we chatted with

about L’Engle in general and Walking on Water specifically. This is a great conversation if you are loving L’Engle and want to dig deeper or if you are hesitant about some of her wonky theology maybe we can ease your minds a bit and point to some beauty she can bring to the conversation of faith and art.With that very long preamble, let’s jump right in to Walking on Water (chapters 5-8)!

(Be sure to “stay” til the end so you don’t miss

Today I am feeling a bit like Mrs. Who from A Wrinkle in Time (also by L’Engle). She is an angel like creature who hilariously “finds it so difficult to verbalize…It helps her if she can quote instead of working out words of her own.” So with that in mind I will be sharing plenty of Madeleine quotes because she says it better than I could!

Probable Impossibles

This chapter title comes from the Aristotle quote, “that which is probable and impossible is better than that which is possible and improbable.” L’Engle says that she has been chewing on that one since college and I think I will be chewing on that one for a long while as well. She then connects this idea to that of religion and the work of the artist. She wishes that the Transfiguration and the Annunciation were celebrated to the same pomp as Christmas and Easter. I’m not sure we are there yet, but I do appreciate the Catholic (and other liturgically minded denominations) have those set aside as feast days!

We are not taught much about the wilder aspects of Christianity. But these are what artists have wrestled with throughout the years.

She makes the argument that if we practice accepting the probable impossible in Christian theology by opening our imaginations to other works of art as well. She points to the incarnation as the best example of the probable impossible. How can this be real?

And what is real? Does the work of art have a reality beyond that of the artist’s vision, beyond whatever has been set down on canvas, paper, musical notations? If the artist is the servant of the work, if each work of art, great or small, is the result of an annunciation, then it does.

I have always been attracted to the idea that the work (if it is truly good) can stand above the artist. It can comprehend truth and goodness that even the artist didn’t intend because the transcendentals go together. If one makes something truly beautiful, then goodness and truth are communicated as well. I think this is what Tolkien was getting at when he talks about sub-creation (the work of the artist participating with God in creation in a smaller way). It is what we are all called to be in various ways because we are made in the image of the creator.

L’Engle then goes on to talk about space (she has already touched on time a bit earlier in the chapter). She says our whole conception of place was turned (literally) upside down when the first astronauts went into space.

…we can either fall apart in terror of chaos or rejoice in the unity of the created universe.

Nonlinear space/time is more easily understood by poets and saints than by reasonable folk.

She says that when she needs stimulation for creativity she goes back to the early church theologians. Then she surprisingly says that she goes to the modern scientists when she needs a more modern voice. This reminded my of A Severe Mercy when Van and Davy found Christianity because they were friends with a lot of kind people, a lot of whom were scientists who also believed in this crazy religion of Christianity. It is fun for me to think about the wonder of the world being opened up to people, not just through theology, but also through the mysteries of the created universe.

Robert Jastrow in his book, God and the Astronomers, talks about the astronomers, after all their questions struggling up to the mountain peak and finding the theologians already there.

Keeping the Clock Wound

L’Engle returns back to the unexplainable that happens outside of the world of Christianity and stories. I love the story about the astronauts hearing the music and the most rational explanation is so unbelievable. Somehow they were hearing the music from back in time. That is amazing! (Also I have watched Interstellar so I am here for this being reality…)

How do you explain it? You don’t. Nor can you explain it away. It happened. And I give it the same kind of awed faith that I do the Annunciation or the Ascension: there is much that we cannot understand, but our lack of comprehension neither negates nor eliminates it.

The title of this chapter comes from a story that L’Engle tells about a town having no clock maker for years and years and then a clock maker finally comes to town and can only fix the clocks that have been wound regularly. Those were the only clocks who could remember to tell time.

So we must daily keep things wound: that is we must pray when prayer seems dry as dust; we must write when we are physically tired (hello first week of school), when our hearts are heavy, when our bodies are in pain. We may not always be able to make our “clock” run correctly, but at least we can keep it wound so that it will not forget.

That is amazing advice for me and so I am guessing a lot of you can relate as well. As a tired homeschooling mother of many who wants to craft a beautiful life full of religious practice and reading and writing I can get very discouraged when it isn’t perfect. The reminder to keep my clock wound seems to be a great balance. It won’t always work, but doing nothing isn’t the answer either. This is an image that will stick with me in the tired seasons.

She also muses a lot on time in this chapter. This works well with the clock story. She talks about wasted time and also how to be present in the time we’re given. If you were with us back in 2022 when we read Our Town by Thornton Wilder, you will recognize the scene below. (If you didn’t read it with us I strongly encourage you to read it at your first available convenience. It is a really amazing short play.)

“Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?”

”No. The saints and the poets, maybe. They do some.”

L’Engle is extremely well read and does a great job of bringing certain stories and images to her text in a way that sticks with me. How can I realize life while I live it? How can I be more like the poets and the saints? Madeleine brings me to contemplation and wonder so frequently in these chapters.

A few more quotes and I’ll move on to the next chapter…

Maturity consists in not losing the past while fully living in the present with a prudent awareness of the possibilities of the future.

All of life is story, story unravelling and revealing meaning. Despite our inability to control circumstances, we are giving the gift of being free to respond to them in our own way, creatively or destructively.

It is not easy for me to be a Christian, to believe twenty-four hours a day all that I want to believe. I stray, and then my stories pull me back if I listen to them carefully. I have often been asked if my Christianity affects my stories, and surely it is the other way around; my stories affect my Christianity, restore me, shake me by the scruff of the neck, and pull this straying sinner into an awed faith.

Names and Labels

In the act of creation our logical, prove-it-to-me minds relax: we begin to understand anew all that we understood as children…But this understanding is—or should be—greater than the child’s because we understand in the light of all that we have learned and experienced in growing up.

This idea of becoming child-like without becoming childish seems to run through the texts of so many authors I love…starting with Jesus, followed by Chesterton, Lewis, and Mason. This is a needed reminder for the type A, get it done, rule follower that I am. I truly believe that stories help with this relaxing into a child like wonder while retaining the knowledge of the adult in the real world.

I like that L’Engle goes from this idea into stories for children and gets very upset that authors think they should write worse when writing for children. She even goes as far as to say that if she writes something that adults will struggle with, she gives it to children instead. In some ways they are more equipped to handle hard concepts than adults because their minds still remain open to mystery.

A child is not afraid of new ideas, does not have to worry about the status quo or rocking the boat, is willing to sail into uncharted waters…there is no idea that is too difficult for children as long as it underlies a good story and quality writing.

I did want to pause for a minute and say that Madeleine says in this chapter that she enjoys when people feel comfortable using her first name because they feel as if they already know her through reading her stories. So, on that note, I will keep using her name and not feel a mite bad that I am being too familiar. I accept her blessing.

I will end these chapter musings with a few more quotes and notes on Christian storytelling that I think are important. First, the idea that one doesn’t have to try to be a Christian writer…

…if she is truly and deeply a Christian, what she writes is going to be Christian, whether she mentions Jesus or not…

A note on evangelizing through art (and in normal life):

We draw people to Christ not by loudly discrediting what they believe, by telling them how wrong they are and how right we are, but by showing them a light that is so lovely that they want with all their hearts to know the source of it.

I especially liked the reason she thought The Secret Garden was Burnett’s best book and the image it leaves me with of the modesty of a story’s message…

…because it is a better piece of storytelling, less snobbish, and the message doesn’t show, like a slip hanging below the hem of a dress.

She ends the chapter talking again about how the best way to be a good Christian writer is to focus on the craft of writing, not on the religious and moral practices of good writers one is trying to emulate in the craft.

Onto our last chapter for this week…

The Bottom of the Iceberg

How does one separate the art from the artist? I don’t think one does, and this poses a problem. How do we reconcile atheism, drunkenness, sexual immorality, with strong, beautiful poetry, angelic music, transfigured painting? We human beings don’t, and that’s all there is to it.

This also reminds me of a scene from The Rings of Power that I thought could have come directly from L’Engle!

ELROND What is beauty when it was born in part of evil?

CIRDAN No less beautiful.

ELROND Not to me.

(Cirdan goes on to name beautiful works of art by varying levels of morally corrupt artists)

CIRDAN Judge the work. And leave judgement concerning those who wrought it to the judge who sees all things.ELROND That feels impossible.

CIRDAN It is called humility. And it is difficult for most. But it is the truest form of sight.

(Just a note here to say that I am no Lord of the Rings expert, but from what I understand of the lore, L’Engle’s point stands…but if the show goes a different direction or I have misunderstood the lore, come to book club and argue with me!)

There were a lot of good anecdotes in this chapter. One I was especially excited about was the idea that story can literally alleviate pain. She uses the example of children being read to in hospitals. But it also makes me feel great about my audiobook listening tendencies during pregnancy. It made me wonder about audiobooks on long car rides and children who struggle falling asleep having audiobooks at bedtime. This sparked a lot of ideas for me. When are times I need story to physically bring me out of something difficult? And what about my kids?

The other image Madeleine brings to us in this chapter that has stuck with me is the idea that our eyes (and cameras) can only see upside down and our brain turns it right side up. I knew this as a scientific fact, but she connected it with the artist’s vocation and I really like the way she put it.

Maybe the job of the artist is to see through all of this strangeness to what really is, and that takes a lot of courage and a strong faith in the validity of the artistic vision even if there is not a conscious faith in God.

I don’t want to miss the musings on laughter and taking oneself lightly, but I really must draw this post to an end. I will leave you with a thought I have often and Madeleine words so well…

…the artist is someone who cannot rest, who can never rest as long as there is one suffering creature in this world. Along with Plato’s divine madness there is also divine discontent, a longing to find the melody in the discords of chaos, the rhyme in the cacophony, the surprised smile in time of stress or strain.

It is not that what is is not enough, for it is; it is that what is had been disarranged and is crying out to be put in place. Perhaps the artist longs to sleep well every night…But the artist cannot manage this normalcy. Vision keeps break through and must find means of expression.

I think that maybe it is hard to see the world with such clarity and the artist is working out their salvation by helping the rest of us make sense of it through their art. May God have mercy on their souls and ours. And may we find the humility to let the one who sees all be the judge while we learn to see the world aright through beauty.

And on that (possibly too heavy handed?) note, I hand you off to

so she can lead us through The Father by Caryll Houselander (our second short story for this month).The Father by Caryll Houselander

by

Madeleine L’Engle points out in Ch. 3 of “Walking on Water,” Healed, Whole, and Holy:

“how many artists have had physical problems to overcome, deformities, lameness, terrible loneliness…It is chastening to realize that those who have no physical flaw, who move through life in step with their peers, who are bright and beautiful, seldom become artists.”

It does seem to be true that a great many writers, actors, composers, painters, etc. have experienced a deepening of their creative faculties due to intense personal suffering. For some artists, this deepening seems to come at the expense of their moral or psychological wellbeing; their minds and moral sensibilities strain and sometimes collapse under the weight of their expanded perspective. For precious fewer artists, this suffering and consequent deepening of creative expression seem rather to sanctify, and to radiate that sanctity outwards through their art. Like both Madeleine L’Engle and Graham Greene, Caryll Houselander suffered greatly as a child from terrible loneliness which would shape both her writing and her theology. Yet, unlike Greene, who flirted with both orthodoxy and married women with a comparable lack of commitment, and unlike L’Engle, whose eccentricity valued “openness” far more than organized religion, Houselander actually became more orthodox the more she suffered, recognizing that the artist who clings to the truth despite their suffering might be the brightest and most beautiful thing of all.

Caryll Houselander was born in 1901 in Bath, England. (It is so fun to remember that Bath is a real place that real people have grown up in, and not merely a fictional setting as it sometimes feels when reading Austen’s Persuasion (August 2023) or Northanger Abbey (August 2025)). Caryll’s parents were popular, athletic, and not particularly pious Anglicans; both struggled to understand or sympathize with their daughter’s more sickly and contemplative nature. When Caryll was six her mother converted to Catholicism, and Caryll was also baptized Catholic. Caryll would later call title her autobiography “A Rocking-Horse Catholic” to differentiate herself from the so called “cradle Catholics” who were baptized Catholic as infants.

After her parents divorced when she was nine, Caryll spent several years at a convent boarding school. There she experienced the first of many mystical visions, when she encountered a grieving nun and saw her sorrow manifested as a physical crown of thorns. Upon returning home to help her mother run the boarding house which was their source of income, Houselander encountered a great deal of anti-Catholic persecution. She struggled greatly with anxiety, loneliness, and panic attacks to the point of being considered neurotic, and even left the church for several years before returning to the faith in her twenties.

Her empathy and creativity led her to become an artist, and she enjoyed success as a woodcarver, began writing, and brought art therapy to children suffering in the wake of the first World War. During the second World War, her gift as a counselor and spiritual director became so well known that both doctors and priests would send their most hopeless cases to her, finding that her ability to love her patients and meet them in their suffering worked psychological miracles that their formal training could not replicate.

Yet even as she gained a certain level of notoriety, she refrained from publishing any major works until she was confident in her own ability to see and to convey truth clearly. Caryll knew well from her own experience with mental illness and from her work as a counselor that while suffering can lead to creative insights, the suffering mind can also distort reality in an attempt to make sense of its own pain. She felt the responsibility of the artist to convey truth, even if that meant waiting to publish her writings until she had learned how to suffer well in her own life and through her art. Indeed, she spent nearly all of her twenties and thirties deliberately studying the gospels and practicing works of charity before she chose to publish her first book.

Published in 1941, her first book, “This War is the Passion” channeled her personal suffering into beautiful insights into the life of Christ. In it, she encouraged her fellow Englishmen to view the ongoing war as a participation in Christ’s suffering. Houselander’s most famous work was published a few years later: “The Reed of God,” a powerful and poetic reflection on the life and virtues of the Blessed Virgin. Over the next decade she would write prolifically, lyrically, and mystically about various aspects of the spiritual life.

Despite her mysticism and acute experiences of suffering, Houselander was playful as well as poetic. She loved practical jokes, frequently smoked and drank, and had a mischievous wit. Once, when asked for advice on how best to show charity to one’s neighbor, she teasingly answered:

“I truly believe that the best way to benefit humanity is to make faces in the bus – slightly mad faces, or puttings out of the tongue suddenly at the person opposite. Think of the thrill that gives to countless uneventful lives to whom nothing ever happens! Then they can tell everyone for weeks that they saw a mad woman on the bus, and they can exaggerate this to almost any extent. This form of charity can even be practiced on the way to work.”

L’Engle quotes Chesterton in Ch. 8 of “Walking on Water,” The Bottom of the Iceberg,noting, “Chesterton said that it was by gravity that Satan fell; one sees representations of the devil sneering, but never in a state of levity, merriment, joyous laughter.” Not surprisingly, one of the clearest signs that an artist (or anyone for that matter) has learned to suffer well is that they either retain or develop a clear sense of humor. Caryll’s life exemplifies this, even though it was tragically cut short by breast cancer when she was only 53. Monsignor Ronald Knox wrote in her obituary:

“In all she wrote, there was a candour as of childhood; she seemed to see everything for the first time, and the driest of doctrinal considerations shone out like a restored picture when she had finished with it. And her writing was always natural; she seemed to find no difficulty in getting the right word; no, not merely the right word, the telling word, that left you gasping.

There was nothing pretentious about her work, there was no self in it; you felt she imagined that anybody else could write like that if they tried. Yet every page was invigorating.

How wide her influence was, I have no means of telling. But we who felt it are asking God to grant her, in that new life, the peace she gave us here. Not with long faces, though; she would not like that."

I love the idea of “the telling word,” and I think there are a few in “The Father.” So without further ado, let’s dig in! “The Father” is actually an excerpt from Houselander’s only novel “The Dry Wood,” which is a collection of vignettes that can be taken individually as short stories, or read together to form a cohesive whole. I first encountered this story in a short story class in college, and it has been printed in the collection of short stories: Stories of Our Century. The broader novel is, as Houselander describes it “the story of innocent suffering” as the community of Riverside, London, simultaneously mourns the loss of their parish priest, Fr. Malone, and the impending loss of the beloved child Willie Jewell, who is terribly ill and in great pain. The novel explores the effect of suffering on the individual and on the community as a whole, and contrasts the sanctifying effect of those who suffer well with the contagious and poisoning effect of those who suffer selfishly.

This theme was one of my favorite parts of Crossing to Safety (May 2024), where the reader is shown the part an individual’s suffering can play in the community that is their families and friends. The following quote also seems relevant to our discussion this month on the effect of suffering on the artist and their work…

“Long-continued disability makes some people saintly, some self-pitying, some bitter. It has only clarified Sally and made her more herself.”

Do artists also become more themselves through their suffering? If art communicates universal truths through individual circumstances, then does this “becoming more themselves” ultimately help or hinder the artist in their ability to see and communicate universal truths clearly?

Delving into “The Father,” I feel like I have to shout out to Well Read Mom because they are in the Year of the Father right now. “The Father” aptly does a wonderful job of drawing parallels between various kinds of fatherhood; namely, God’s fatherhood, the spiritual fatherhood of a priest or pastor, and the biological fatherhood of the family patriarch are all present in the story. In each case, we see the father guide, forgive when guidance is stayed from, and love their children despite their failings.

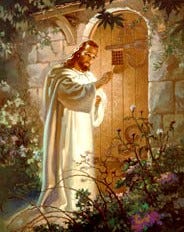

One of my favorite scenes in this story is the knocking scene, where Fr. O’Grady is waiting for entrance to the Fernandez house. It reminds me of the famous image of Christ knocking on the door with no outward knob, symbolizing the soul which must consent to let Him in.

The first time Fr. O’Grady knocks is related simply: “He knocked gently, and waited.” The second builds momentum:

“Fr. O’Grady knocked again, a knock which he knew fell like a blow on the mind of the listener inside, but even by its gentleness proclaimed a patience which could not ultimately be refused.”

The rhythm of the knocking and the contrast between the persistent gentleness of the pursuer and the fear of the pursued also reminds me of the “The Hound of Heaven” by Francis Thompson, where Divine Love hunts its object like a hound pursuing its quarry, with rhythmic and unrelenting footfalls:

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

But with unhurrying chase,

And unperturbèd pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

They beat—and a Voice beat

More instant than the Feet—

'All things betray thee, who betrayest Me'.

In Houselander, as in Thompson, the love of a Father illustrates that that “Fear wist not to evade, as Love wist to pursue.” When Fr. O’Grady is finally admitted, his love and care for his flock become quickly apparent in his ministry to Fernandez, his intersession for Carmel, and his provisions for Teresa.

The parallels between the Fernandez house and the souls of its inhabitants don’t end at the door. The false dichotomy between piety and joy has pervaded the spiritual life of the Fernandez family to such an extent that even the furniture has been affected! The furniture is described as

“too big for the room, and too much. It was oppressive, and spoke silently of larger, more spacious rooms, of greater expanse of light and wider skies, of more space even for human thought and human passion. It was old furniture, ornately carved in dark wood and polished by the constant touch of centuries of caressing, possessive hands. It was, however, wanting in comfort. There was no sofa, not a cushion, nowhere to relax.”

The two religious artifacts owned by the Fernandez family likewise illustrate that piety and joy should not be mutually exclusive. On the one hand, the crucifix shows “nothing of the mysterious joy of immolation… the emphasis of a terrible beauty stressed only the torment of the suffering man-God.” On the other hand, the wax statue of Our Lady is florid, dressed in silk, and holding a laughing Christ-child. One is not a more true representation of Christ than the other, though the tone of the first has clearly been embraced by the Fernandez family over the tone of the latter. Yet a healthy Christianity has room for “the pipe, the pint, and the cross,” as Chesterton famously said. Joy and even physical pleasure are not antithetical to holiness. Indeed, as O’Grady preaches to Fernandez:

“God does not just give His children necessities. You have read the Sermon on the Mount. He clothes His children, but He is interested in clothing each one beautifully, like the lilies of the field. He feeds them, and is their food. But even Himself as food, is given in loveliness, the goldenness of wheat, the whiteness of bread. He does not only give our needs; He is extravagant, almost profligate, in love. Yes, Fernandez, look at the millions of stars, look at the leaves, at the grass, at the daisies, and look at all the countless millions of seeds, wasted, that one take root to be a tree for us! You see, Fernandez, all creation is only one thing, a father clothing and feeding, delighting his child, and saying again and again in everything, ‘I am your father, I love you!’”

Fr. O’Grady challenges Fernandez to forgive and love his daughter as God the Father forgives and loves his children. In the end, Fernandez does realize that “He wanted to break through the torment of pride, to forgive, to learn to laugh, to enjoy life, to delight in his child.” One is left with the hope that an “Indian summer” might be in store for the souls of Fernandez and Carmel as well as for Teresa. Through Fr. O’Grady, Houselander challenges you, the reader, likewise not to “shut the door on your happiness; it’s ajar… open it wide.”

Some closing thoughts that I’d love to discuss with you all at book club, whether in person or virtually:

- Fernandez undoubtedly loved Carmel throughout her life, yet struggled with translating that love into something a child could actually feel. Often mothers excel in providing this more tangible “felt” love within the home. How is the love of a father different from that of a mother? How do these differences affect how we view God, who we call Father? Is it mere anthropomorphism to view God as masculine as L’Engle believes? Or is truly more fitting to view God as masculine rather than feminine, and as a father rather than as a mother?

- Writers who are particularly intent on conveying truths about objective reality in their art are all too aware that their readers are often so overwhelmed with facts that they are almost immune to truth. These writers often develop favored techniques for grabbing their readers attention and forcing them to confront truths that otherwise might escape them. Chesterton’s go-to technique was to use paradoxes. He is quoted as saying “Paradox has been defined as Truth standing on her head to get attention.” Flannery O’Connor favored the grotesque as a means of “drawing large and startling figures for the almost blind.” Caryll Houselander favored the poetry of the “telling word” that “leaves you gasping” and unable to deny the truth presented. Who are your favorite truth tellers? And what tricks do they employ?

Thanks again to Sarah Van Hecke for that reflection on our second short story! That is all we have for now. I definitely encourage you to read the short story, read Sarah’s reflection and questions, and then read the story again. Revisiting each story will give deeper insights and, I think, lead to great discussion in a few weeks! Here is the schedule for the posts this month:

August 21- Introduction to Walking on Water and each short story

August 28- Waking on Water Ch. 1-4 (pgs 1-68) and The Hint of an Explanation by Graham Greene

September 4- Walking on Water Ch. 5-8 (pgs 69-135) and The Father by Caryll Houselander (you are here)

September 11- Walking on Water Ch. 9-12 (pgs 136-190) and First Confession by Frank O’Connor

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, I appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running and I appreciate it!