Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

Welcome back to our wanderings through the colorful and spirited lands of nineteenth century New Mexico. Though our trails may be winding, they are not without purpose toward the universal order that leads to eternal life. As Tolkien says in The Fellowship of the Ring, “Not all those who wander are lost.” And though no map of this vast land has yet been charted, back in the Prologue Bishop Ferrand graciously provided us with a compass to guide our reading when he stated that the Vicar “must be a man to whom order is necessary- as dear as life” (p. 8). The chapters in this middle portion of the novel bring into view the importance of those words as we find Father Latour and Father Vaillant in the depths of their ministry confronting disorder in its many forms.

Book 4

The title of this section, “Snake Root,” gives us a sense of the dark past that we are to encounter in these chapters with the stories of the religious practices of the Pecos tribe, said to include snake worship and possibly child sacrifice. Father Latour is unsure of how much credence to give the stories he has heard but does have a disturbing experience while inside their ceremonial cave. From the strange behavior of his guide, Jacinto, “standing on some invisible foothold, his arms outstretched...his ear over the fresh patch of mud, listening...he looked to be supported against the rock by the intensity of his solicitude” (p. 131), to the chilling, odorous breath of the mouth-shaped cave and the disorienting flood-like noise of the underground river, Father Latour is unable to make much sense of the event. Ultimately, he concludes, “neither the white men nor the Mexicans in Santa Fe understood anything about the beliefs or the workings of the Indian mind” (p. 133).

Cather’s descriptions of the cave, though intense and not lacking in quantity, retain a quality which is vague and unsettling, as if we are hearing the “stone lips” whispering unintelligible secrets of the Indian rituals. We are also met here with an eerie contrast to the relationship between man and nature that we saw in the first section of the book with the cruciform tree as means by which Father Latour is aided in his worship of God. In the darkness of the cave, however, the relationship appears to be inverted from that purpose, made to work as an instrument for the dwelling and worship of other spirits.

I must confess that this part of the story has proven challenging to write about because my thoughts on it seem to me to be as scattered and incohesive as the numerous cultures and customs throughout the Bishop’s great diocese. But, just as Father Latour is left unable to fully understand how such a dreadful cave likely saved his life, perhaps we too do not need to fully comprehend these episodes for them to inform our understanding.

Book 5

This section marks the middle of the nine-book structure and hinges on Father Latour and Father Vaillant’s efforts to combat vices, almost personified, among the priests in these chapters. We see the uncurbed lust of Padre Martinez, having fathered numerous children and publicly “denying the obligation of celibacy for the priesthood” (p. 159). Then there is Father Lucero’s consuming greed, as displayed by his miserly habits and the brutal murder of a man who tried to steal his hoarded fortune. “He had the lust for money as Martinez had for women” (p. 161). Father Lucero’s disordered attachment also announces itself when he buries the money Padre Martinez entrusted to him for Requiem Masses. This passage seems something of an echo of “The Parable of the Talents” in the Gospel of Matthew (25:14-30) in which a servant buries the money his master entrusted to him instead of investing it for beneficial purposes.

Here we refer back, once again, to Bishop Ferrand’s excellent foresight when he insisted on the appointment of a nonnative priest to preside over the territory. For when Father Latour makes his way to Taos to contend with the infamous Padre Martinez, he finds him to be “dictator to all the parishes in northern New Mexico, and the native priests at Santa Fe were all of them under his thumb” (p. 139). While Father Latour acknowledges that Padre Martinez possesses many qualities to be a great man, he also perceives the disorder that is obstructing his views on the teachings of the Church, much like that of Padre’s house “piled so high with books that they almost hid the crucifix hanging behind it,” (p. 143). Consequently, Father Latour, not under Martinez's control or intimidated by his threats, resolves to replace him. However, upon seeing the size and devoutness of the congregation, he decides to wait until he can make arrangements for a Spanish priest, whom the people will more likely respect, to take the place of Padre Martinez. In doing so, Father Latour seems to take a page from the parable of “The Weeds among the Wheat,” also in the Gospel of Matthew (13:24-30), when he explains to Father Vaillant, “I do not wish to lose the parish of Taos in order to punish its priest” (p. 157).

Cather’s descriptions of the landscape in these pages strike a different chord than some of the ones we looked at in the first sections. Here she speaks of the mountains, rising sharply out of the land, imprinted with ravines and canyons, “like symbols; serpentine...the seat of old religious ceremonies...the repository of Indian secrets” (p. 151), almost as if they are graven images carved out by the deep-seated rituals and customs of the native peoples. Similar to what we saw with the Pecos tribe, nature is highly honored and respected among them, but, like all idol worship, in a disordered fashion.

Book 6

Within these chapters we shift from the inordinate vices of parish priests wreaking havoc in Book Five to the smaller, seemingly harmless, vanity of one woman. Dona Isabella's tight grasp on her vanity nearly destroys an opportunity for her to honor her late husband’s wishes, claim parentage of her daughter, and provide financial support for herself and many who are dependent on her. Only after much prompting is she able to loosen her grip just long enough to secure the good of many, and then just as quickly retightens her hold. In light of this story we may well tremble at the thought of our own pet vices and seriously consider Father Vaillant’s words when he says that even after all the spiritual battles he has fought in his time, he would rather “combat the superstitions of a whole Indian pueblo than the vanity of one white woman.” (p. 192).

We also learn of Father Latour’s great ambition to build a cathedral in Santa Fe that “might be a continuation of himself and his purpose” (p. 175). In this we are reminded of the legend of Fray Baltazar whose ambitions for a grand church came to be of little use for the needs of the people. Though there are many differences between these two priests, we await to see how Father Latour’s purposes will play out.

Throughout the novel we have heard numerous stories of revolts, battles and massacres detailing the animosity and prejudices between the American, Mexican and Indian races all dwelling in the same land. Each has their own language and set of customs, and none want interference in their affairs from any of the others. Amid the disorder of clashing cultures, we come to understand Father Latour’s unique position in which he may be a unifying force through the ministry of the Church, promoting spiritual order so as to encourage the people to set aside the idea of one man against or dominating another and become acquainted with the concept of one God with all people.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, we have had to leave many paths in these pages unexplored as time and ability are ever limiting factors in such matters outside of heaven. So we will conclude our meanderings for now and, where our resources end, allow the Lord's grace to begin. Until our next excursion, fare thee well.

Death Comes for the Archbishop Reading Schedule

Wednesday, April 16th: Introduction/Reading Schedule

Monday, April 21st: Reading Revisited ep. 47: Intro to Death Comes for the Archbishop w/ Brittney Hawver and Elise Boratenski

Wednesday, April 23rd: Prelude and Books 1-3

Wednesday, April 30th: Books 4-6

Wednesday, May 7th: Books 7-9

Monday, June 9th: Reading Revisited ep. 58 - Revisiting Death Comes for the Archbishop

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

On the Podcast:

What We’re Reading Now/Next:

May

Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather

June

Trust by Hernan Diaz

July

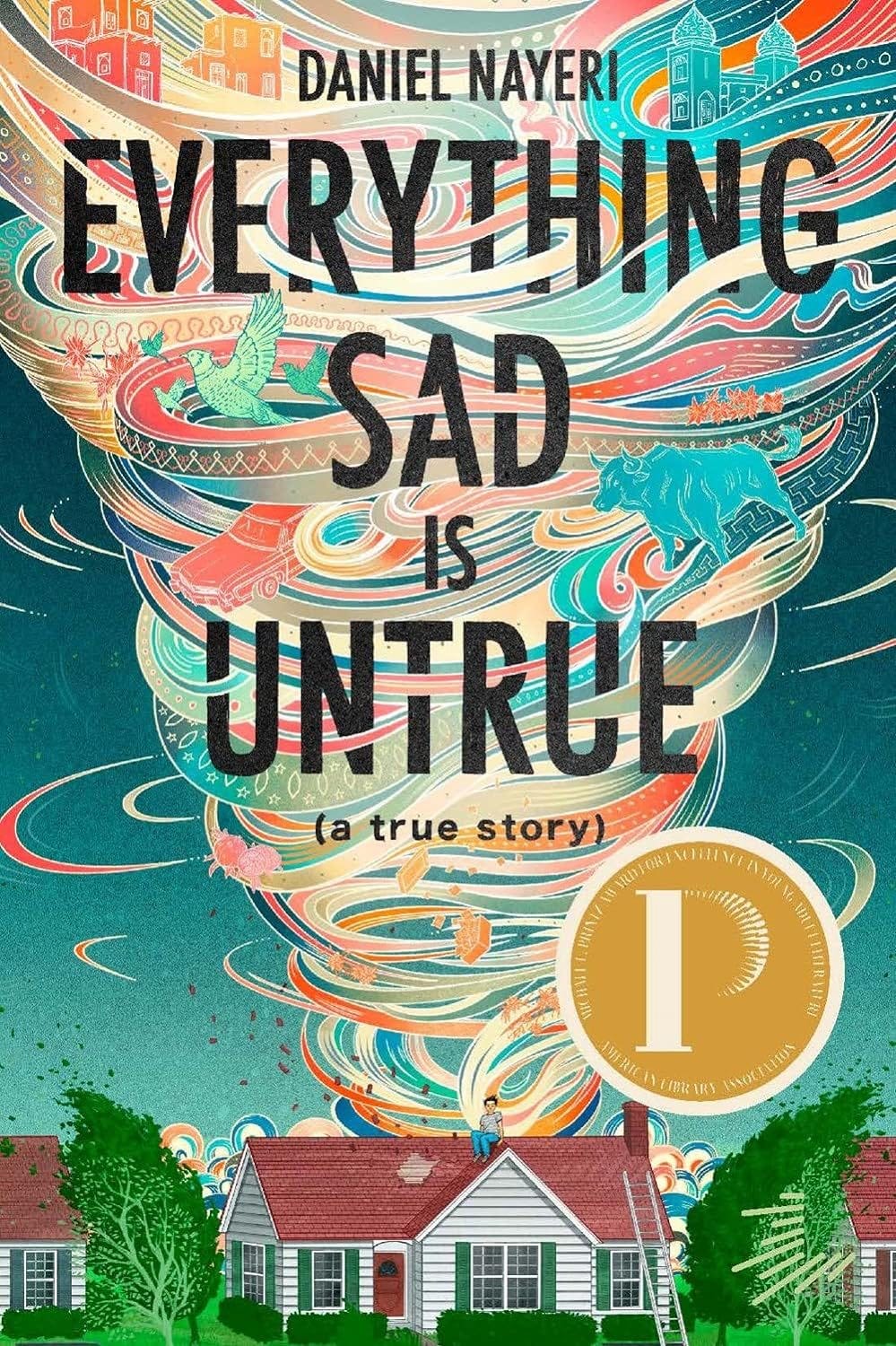

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

We have turned on paid subscriptions which will allow you to support the work we are doing here as well as receive Read Along Guide PDFs each month, voice recordings of the Read Along Guides and Essays, and we are working on (printable) bookmarks for each book.

If you would like to make a small contribution to the work we’re doing here at Reading Revisited, we invite you to do so with the Buy (Us) a Coffee button below. We so appreciate your support!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, we appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running, and we appreciate it!