Welcome to Reading Revisited, a place for friends to enjoy some good old-fashioned book chat while revisiting the truth, beauty, and goodness we’ve found in our favorite books.

Welcome to our last sojourn together through the storied life of Father Latour. As is the way of all novels, and as the title itself forewarned us, we have come to the final chapters and are approaching the end. Just as Father Latour spends his last days “in the middle of his own consciousness; none of his former states of mind were lost or outgrown. They were all within reach of his hand, and all comprehensible” (p. 288) so may we, having finished reading, with the whole of the book in mind, aspire to such awareness as we close out our time in this novel.

Book 7

We have seen much of the external difficulties Father Latour has faced up to this point; but, it is here we discover some of the internal struggles as he endures, “one of those periods of coldness and doubt” (p. 210). The phrase “dark night of the soul” originates from a poem written by St. John of the Cross that speaks of a period of time in one’s life of deep spiritual dryness in which God seems to have withdrawn Himself from one’s soul, similar to Christ’s feeling of being forsaken by God on the Cross. Many saints are said to have experienced this sense of abandonment to some degree on their path to sanctity as it is a means by which to surrender oneself to the Divine Will. Father Latour’s spiritual state certainly seems to mirror this idea as “his prayers were empty words and brought him no refreshment. His soul had become a barren field” (p. 211).

Despite these spiritual troubles, however, we find that Father Latour is not left without aid. From the first chapters of the novel, we have seen traces of Mary’s intercession woven throughout the story; and in this section we find her comforting Father Latour in a profound and poignant way through the faithfulness of the Mexican slave, Sada. It is by this woman’s witness that he comes “so near to the Fountain of all Pity...the beautiful concept of Mary pierced the priest’s heart like a sword” (p. 217). The moon is an ancient symbol of Mary as she is said to reflect the light of Christ just as the moon reflects the light of the sun. It is fitting then, that right after this encounter, the light of a full moon breaks through the clouds to embrace Father Latour like a mother consoling her distressed child.

Another instance of Father Latour’s internal struggles arises in the form of a reversal from our encounter with Father Vaillant in the first chapters, when he is reluctant to venture further into the New World as he repeatedly insisted “this is far enough.” Now it is Father Latour who has reservations about Father Vaillant’s great desire to search for lost Catholics by going “from house to house... to every little settlement” (p. 206). These themes of Father Latour’s sense of abandonment and consolations will continue to wind their way through the rest of the novel.

There is also a brief story in which, if we have “ears to hear,” we may catch echoes of the objective correlative we observed in the first section with the lost El Greco painting. Father Vaillant relates the story of the Pima Indians, who for generations had hid away the sacred objects for celebrating Mass in a cave, “like a buried treasure; they guard it, but they do not know how to use it to their soul’s salvation” (p. 207). He takes great pleasure in being able to recover and “restore to God his own” (p. 207), just as had been the hope when he and Father Latour were sent to the New World.

Book 8

In this section Father Latour brings together his love for the beauty of both the Church and the landscape when he chooses a hill of yellow rock, hidden like a sacred gem, “very much like the gold of the sunlight” (p. 239), with which to build his beloved cathedral. It is as if he is officiating a marriage between the land and the Faith as he recognizes the value of such a union when he remarks, “I would rather have found that hill of yellow rock than have come into a fortune to spend in charity” (p. 242). The hope that it will be a lasting landmark, a beacon for the faithful for generations to come, is evident by his commissioning the cathedral to be built in a Romanesque style which is known for its thick, strong walls as well as great arches and towers. This choice of architecture not only reflects his love for his homeland, allowing him to sow some of its cultural beauty in the New World, but is even perhaps a symbolic transplanting of himself in this new land as his very name, Latour, means tower.

Then we come to a sad parting between long-time friends. And though a sense of loneliness may well be expected in such times, Father Vaillant realizes that Father Latour is grappling with a more profound sense of isolation as he reflects:

Wherever he went, he soon made friends that took the place of country and family. But Jean, who was at ease in any society and always the flower of courtesy, could not form new ties. He was like that even as a boy; gracious to everyone, but known to very few (p. 251).

In the midst of his suffering, we find Father Latour once again taking up his habit of turning his mind to Christ’s sufferings as he contemplates, “It was just this solitariness of love in which a priest’s life could be like his Master’s” (p. 254). And Father Vaillant, as he rides away, appeals to Mary to console Father Latour with an exclamation of “Auspice Maria,” a Latin phrase meaning under the protection of Mary. This idea is promptly brought to life in Father Latour’s mind as he considers just after Father Vaillant’s departure, “life need not be cold or devoid of grace in the worldly sense, if it were filled by Her who was all the graces” (p. 254).

Book 9

Much has been detailed throughout the novel about the Indians’ unique regard for nature. And though Father Latour never affects a clear reconciliation between their beliefs and that of the Faith, it seems as though he has found an occasion for hope while he reflects on his encounters with them over the years. Manuelito gives a passionate representation of the Navajo’s connection with the land, explaining that “their country...was part of their religion...it had nourished and protected them; it was their mother” (p. 292). These ideas relate in some sense to Father Latour’s own experience as he, himself, has witnessed the Holy Mother’s intercession throughout the land, and, as we found in the very first chapters, he holds a belief that miracles are worked within the order of nature. As such, we can perhaps detect a deeper meaning when Father Latour relates his thoughts about the Indian’s survival in their native lands, “I do not believe as I once did, that the Indian will perish. I believe that God will preserve him” (p. 296).

As Father Latour enters the last chapter of his life, the cathedral he commissioned has been completed and his archbishopric retired. Having purchased some land, he now spends his time setting out “an orchard which would be bearing when the time came for him to rest” (p. 263). Father Latour is also setting out a figurative orchard as he trains new priests whose lives will bear fruit among the land when he is gone. He quotes to his trainees Pascal’s words “that Man was lost and saved in a garden” (p. 265); and we find that this story also began in a garden at the Cardinal’s house in the Old World and is ending in the garden Father Latour is growing in the New World.

Though proudly originating from the Old World, Father Latour has put down roots in the New World and has adapted to the environment to such a degree that when he is back in the Old World visiting, “he found himself homesick for the New” (p. 272). Like Moses, he has wandered desert lands for nearly forty years, and, longing for its untamed air, has “come back to die in exile for the sake of it” (p. 273). He sees the red hills as “not the color of living blood...but the color of the dried blood of saints and martyrs” (p. 270), a land to which he also has given his life. He has made his way from the Old World to the New World and is now preparing to enter into that Unending World.

As he approaches the end, Father Latour is “living over his life” (p. 281) and feels perhaps some sense of failure as he “often said his diocese changed little except in boundaries” (p. 284). His final struggle consists in adapting his sensibility “to the shape of things,” as we have explored previously, to that of the shape of eternity. We refer back to his own words on miracles as, “perceptions being made finer, so that...our eye can see and our ear can hear what is there about us always” (p. 50) and recognize that death is but that final miracle playing out inside Father Latour. Though he may not yet be able to see the fruit of his life’s work, it is ripening in his last moments as we see in the parallel between his assistance of Father Vaillant struggling to leave his homeland to become the great bishop he was meant to be, and himself now “being torn in two...by the desire to go and the necessity to stay...trying to forge a new Will in that devout and exhausted priest” (p. 297).

Conclusion

With Father Latour’s conclusion in this life, we also must conclude our time in this book. It has been a pleasure wandering with you. Though we have covered much territory, we have had to leave so much unexplored. But, we may take comfort in the thought that just as God is outside of time, so we are outside of the book's timeline and may revisit its wonders whenever we please. That is, until we, like Father Latour, are called out of time and into eternity. For who can say what wonders await us then?

Death Comes for the Archbishop Reading Schedule

Wednesday, April 16th: Introduction/Reading Schedule

Monday, April 21st: Reading Revisited ep. 47: Intro to Death Comes for the Archbishop w/ Brittney Hawver and Elise Boratenski

Wednesday, April 23rd: Prelude and Books 1-3

Wednesday, April 30th: Books 4-6

Wednesday, May 7th: Books 7-9

Monday, June 9th: Reading Revisited ep. 58 - Revisiting Death Comes for the Archbishop

Until next time, keep revisiting the good books that enrich your life and nourish your soul.

In Case You Missed It:

On the Podcast:

What We’re Reading Now/Next:

May

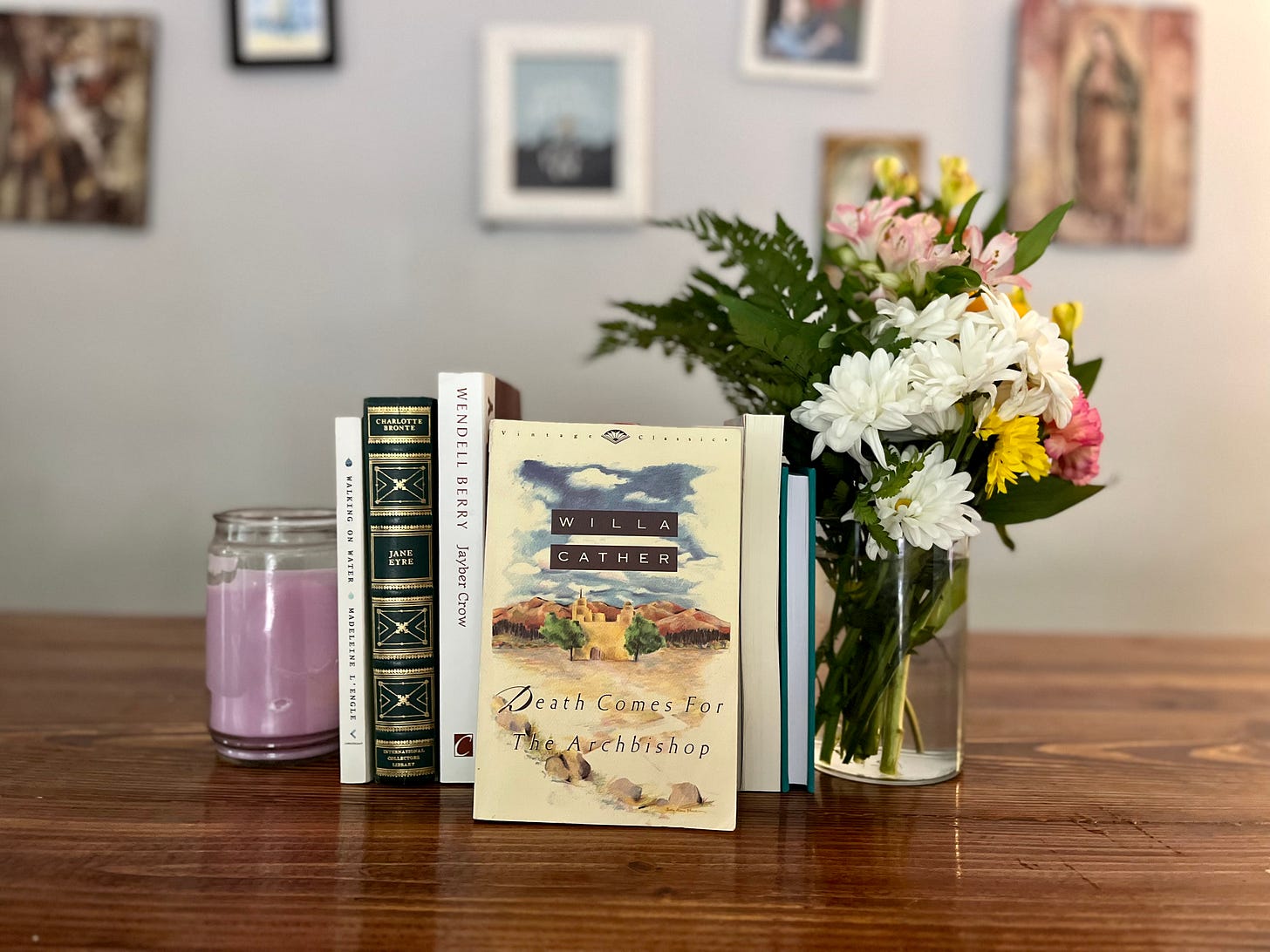

Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather

June

Trust by Hernan Diaz

July

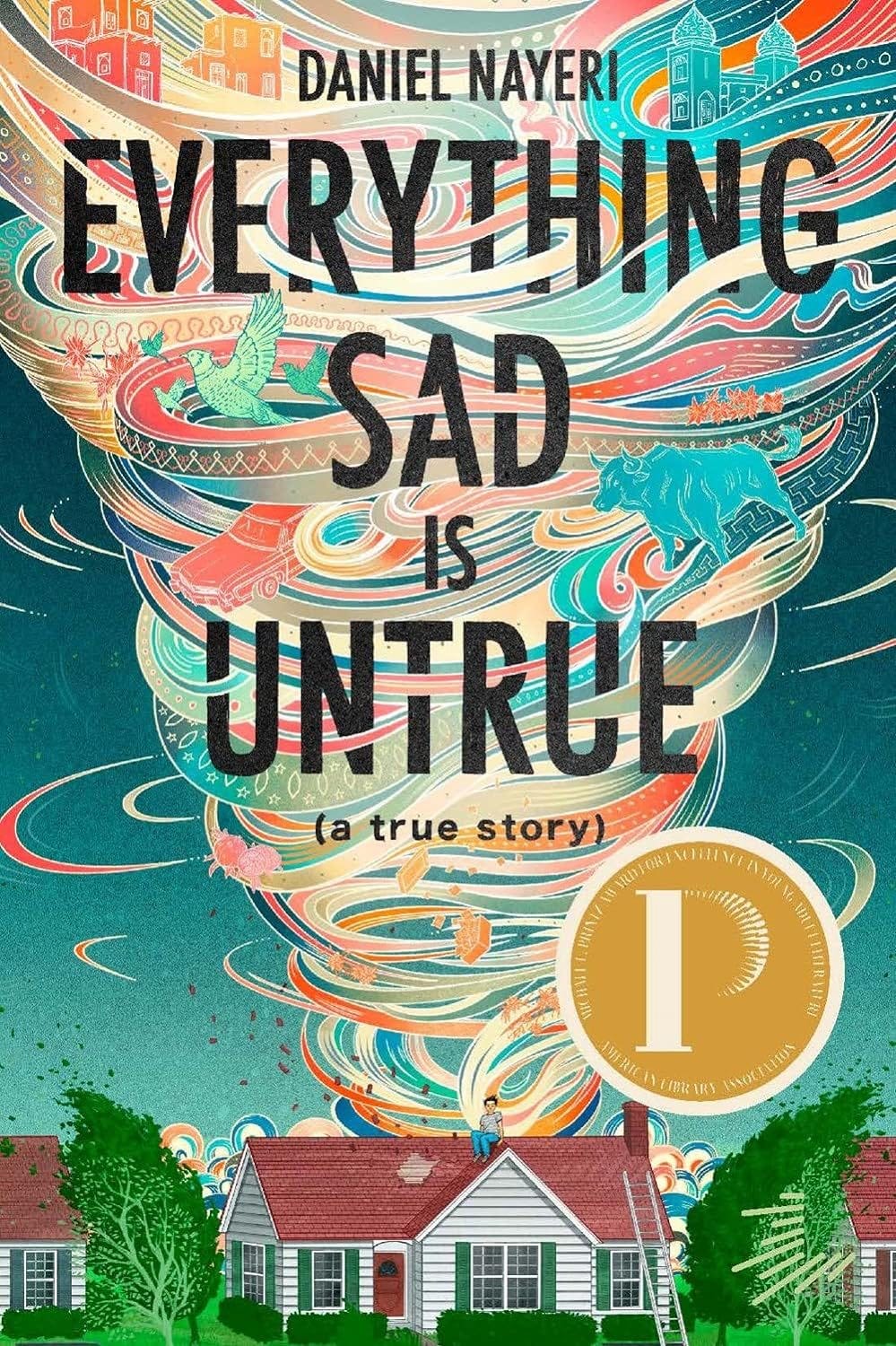

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri

A Few Reminders:

If you are wanting to get in on the in person or virtual community please contact us!

We have turned on paid subscriptions which will allow you to support the work we are doing here as well as receive Read Along Guide PDFs each month, voice recordings of the Read Along Guides and Essays, and we are working on (printable) bookmarks for each book.

If you would like to make a small contribution to the work we’re doing here at Reading Revisited, we invite you to do so with the Buy (Us) a Coffee button below. We so appreciate your support!

*As always, some of the links are affiliate links. If you don’t have the books yet and are planning to buy them, we appreciate you using the links. The few cents earned with each purchase you make after clicking links (at no extra cost to you) goes toward the time and effort it takes to keep Reading Revisited running, and we appreciate it!